A Review of Jordan's Principle

March 2019

Evaluation, Performance Measurement

and Review Branch

Audit and Evaluation Sector

PDF Version (552 Kb, 59 Pages)

Table of contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1. Background

- 2. Scope of Work

- 3. Case Studies Issues and Questions

- 4. Selected Case Studies

- 5. Methodology

- 6. Key Findings

- 7. What are the Key Strengths and Challenges, and what are the Lessons Learned?

- Appendix A: My Child, My Heart Case Report

- Appendix B: Choose Life Case Report

- Appendix C: Early Childhood Intervention Program Regina Case Report

Acronyms

| CDW |

Child Development Worker |

|---|---|

| CHRT |

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal |

| ECE |

Early Childhood Educators |

| ECIP |

Early Childhood Intervention Program |

| FNIHB |

First Nations and Inuit Health Branch |

| FTE |

Full-Time Equivalent |

| ISC |

Indigenous Services Canada |

| INAC |

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada |

| KOSSS |

Keewaytinook Okimakanak Secondary School Services |

| NAN |

Nishnawbe Aski Nation |

| OT |

Occupational Therapy |

| PT |

Physical Therapy |

| SLP |

Speech Language Pathologists |

| SSF |

Specialized Support Facilitators |

Executive Summary

Background and Methodology

Jordan's Principle originated in 2007, stemming from the inequities in services First Nations children were receiving on-reserve in comparison to their non-First Nation counterparts. Jordan's Principle includes a $382 million dollar commitment over three years (2016‑2019) on behalf of the Government of Canada to enable service coordination, service access resolution, data collection and capacity building to ensure that First Nations children, regardless of on- or off‑reserve status, receive equitable treatment and access to government funded services.

R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. was contracted to complete a Review of Jordan's Principle. The Review was not intended to be a full evaluation of Jordan's Principle, but rather, to identify how projects funded by Jordan's Principle were implemented in some communities, including the identification of challenges, successes and the lessons learned in those communities.

Completed in a compressed timeframe, the Review site visits occurred between August to September 2018, and the analysis and reporting took place from October to November 2018. Two of the three case studies assessed Jordan's Principle funding that was provided to expand and enhance pre-existing programming (i.e., My Child, My Heart, and the Early Childhood Intervention Program (ECIP), while one of the case studies reflected the experiences of an entirely new program (Choose Life). My Child, My Heart, provides case management of services to children 0-21 with severe needs, which includes the provisioning of services to their families as needed. ECIP was established in Saskatchewan in 1980 to provide services to children with developmental delays; Jordan's Principle funding allowed the extension of services from children aged 0 to 6 to children and youth aged 6 to 17. Choose Life projects were designed to address mental health and resilience issues among youth in northern Ontario, as this area has largely experienced a high rate of youth suicides in the past.

Case studies completed as part of the Review (My Child, My Heart; the Early Childhood Intervention Program; and Choose Life), included a review of available program documentation, a two to three day site visit to the program delivery location, a development of a community profile, and interviews and focus groups with program staff, stakeholders and parents. Findings from the Review are limited in that only a very small proportion of funded projects were examined, and short timelines meant administrative data was not available, project documentation was limited, and data collection was completed with stakeholders who were available at the time of the site visit.

Review Findings

Operating Context and Service Gaps

Projects that had existing infrastructure or were extensions of existing projects experienced fewer implementation challenges than did new projects. Generally, projects that were new lacked a solid understanding of program design, program theory (linking activities to outcomes), assessment and intake procedures, case management processes, assessment and measurement processes, and development of service plans. When located in rural or remote locations, programs also struggled with the availability of qualified and trained staff in the community and availability of other resources (training, referral service providers, etc.). Across all sites, the lack of funding for youth older than 17 years of age was noted as the major service gap.

Roles and Responsibilities

Roles and responsibilities among partner organizations or other community service providers were best documented in pre-existing programs. While relationships existed between the project and some primary partners, program design was not based on an extensive consultation with all stakeholders and/or service partners. Consultation and communication had occurred between the funded projects and other stakeholders, but such consultation was generally initiated by project staff during informal case management rather than as part of a formal communication/outreach strategy.

Service Delivery Similarity Across Funded Projects

Each of the five projects reviewed had considerable variation in program consultation, design, implementation and execution. Most had enhanced or aimed to enhance case management, most had introduced new program activities, all had some focus on providing parents supports (although it was limited), and all had introduced some new staff, while two used existing staff and support services.

Changes Under Jordan's Principle for Children Families

Jordan's Principle funding appeared to have positive outcomes for children and their families. Case study participants identified a range of outcomes such as a reduction of negative incidents among youth, improved school attendance, the ability for families to remain living on‑reserve, and improved supports for parents. More specifically, parents noted that of significant benefit was the: introduction of an active champion who helped assess and meet the needs of their children, positive child outcome from the supports provided (e.g. improved ability of their child to communicate their needs when they are non-verbal), and improved educational outcomes.

Jordan's Principle Contribution to Improved Service Coordination or Partnerships

Coordination of services was likely improved under Jordan's Principle, but for the projects that were visited, a high degree of service coordination was not observed (although relationships exist with referral agencies). As part of the program roll-out, programs undertook consultations with communities and service providers as to program objectives and elements; however, programs were not always designed in a stepwise manner (program coordination and consultation, funding for program design, and funding for program implementation).

Key Strengths

Generally all programs provided new funding to fill gaps in services and programs were designed to meet local/community need. Similarly, parents were provided with needed supports that were otherwise missing. An important strength of Jordan's Principle noted by stakeholders was the rapid and timely approval of funding (for families) and the high level of project approval.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned included:

- Program effectiveness was impacted by the operating time, the availability of resources to design and implement programming, and the availability of resources and staff to maintain programming.

- Programs require support in developing program theory to link program activities to intended outcomes. Further, programs require support in measuring and monitoring these outcomes.

- More guidance should be provided to programs to allow program implementation to occur in a stage wise approach that includes community consultation, program design and program roll-out.

- Capacity and infrastructure challenges can be addressed at a high level through "tool‑kits" and training.

1. Background

1.1 Overview

This report summarizes the key findings associated with the Review of Jordan's Principle, initiated by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) in the summer of 2018. This Review is not intended to be a full evaluation, but rather, is intended to identify how Jordan's Principle was implemented in some communities, to identify challenges and successes, and provide some insights as to lessons learned in these communities. It should be emphasized that results cannot be generalized to all activities funded under Jordan's Principle, as the researchers were only able to conduct reviews of five projects in three different jurisdictions. Thus, given that there were hundreds of projects funded, the case studies represent only a fraction of all projects supported by Jordan's Principle.

1.2 Jordan's Principle

Jordan's Principle originated in 2007 stemming from a formal complaint on behalf of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations; this complaint was directed to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) regarding the inequitable services First Nations children were receiving in comparison to their non-First Nation counterparts.

Jordan's Principle arose from the experience of Jordan River Anderson, a First Nations boy from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. Jordan had severe medical issues, including a rare disorder, and was consequentially hospitalized from birth. Jordan passed away at the age of 5 before getting an opportunity to live in a medical foster home, as the provincial and federal government disputed who has financially responsibility for Jordan's care.

In order to resolve jurisdictional disputes involving the care of First Nations children, the House of Commons of Canada adopted a motionFootnote 1 in December 2007, called Jordan's Principle. This principle provides that "where a government service is available to all other children, but a jurisdictional dispute regarding services to a First Nations child arises between Canada, a province, a territory, or between government departments, the government department of first contact pays for the service and can seek reimbursement from other governments or department after the child has received the service."Footnote 2 This principle essentially seeks to prevent First Nations children from being denied essential public services or experiencing unreasonable delays in receiving such services.

On May 26, 2017, and amended on November 2, 2017, the CHRT issued a ruling that included an expanded definition of Jordan's Principle:

"[2] In recognition of Jordan, Jordan's Principle provides that where a government service is available to all other children, but a jurisdictional dispute regarding services to a First Nations child arises between Canada, a province, a territory, or between government departments, the government department of first contact pays for the service and can seek reimbursement from the other government or department after the child has received the service. It is a child-first principle meant to prevent First Nations children from being denied essential public services or experiencing delays in receiving them. On December 12, 2007, the House of Commons unanimously passed a motion that the government should immediately adopt a child-first principle, based on Jordan's Principle, to resolve jurisdictional disputes involving the care of First Nations children."

"[135]…Canada's definition and application of Jordan's Principle shall be based on the following key principles:

- Jordan's Principle is a child-first principle that applies equally to all First Nations children, whether resident on or off reserve. It is not limited to First Nations children with disabilities, or those with discrete short-term issues creating critical needs for health and social supports or affecting their activities of daily living.

- Jordan's Principle addresses the needs of First Nations children by ensuring there are no gaps in government services to them. It can address, for example, but is not limited to, gaps in such services as mental health, special education, dental, physical therapy, speech therapy, medical equipment and physiotherapy.

- When a government service, including a service assessment, is available to all other children, the government department of first contact will pay for the service to a First Nations child, without engaging in administrative case conferencing, policy review, service navigation or any other similar administrative procedure before the recommended service is approved and funding is provided. Canada may only engage in clinical case conferencing with professionals with relevant competence and training before the recommended service is approved and funding is provided to the extent that such consultations are reasonably necessary to determine the requestor's clinical needs. Where professionals with relevant competence and training are already involved in a First Nations child's case, Canada will consult those professionals and will only involve other professionals to the extent that those professionals already involved cannot provide the necessary clinical information. Canada may also consult with the family, First Nation community or service providers to fund services within the timeframes specified in paragraphs 135(2)(A)(ii) and 135(2)(A)(ii.1) where the service is available, and will make every reasonable effort to ensure funding is provided as close to those timeframes where the service is not available. After the recommended service is approved and funding is provided, the government department of first contact can seek reimbursement from another department/government;

- When a government service, including a service assessment, is not necessarily available to all other children or is beyond the normative standard of care, the government department of first contact will still evaluate the individual needs of the child to determine if the requested service should be provided to ensure substantive equality in the provision of services to the child, to ensure culturally appropriate services to the child and/or to safeguard the best interests of the child. Where such services are to be provided, the government department of first contact will pay for the provision of the services to the First Nations child, without engaging in administrative case conferencing, policy review, service navigation or any other similar administrative procedure before the recommended service is approved and funding is provided. Clinical case conferencing may be undertaken only for the purpose described in paragraph 135(1)(B)(iii). Canada may also consult with the family, First Nation community or service providers to fund services within the timeframes specified in paragraphs 135(2)(A)(ii) and 135(2)(A)(ii.1) where the service is available, and will make every reasonable effort to ensure funding is provided as close to those timeframes where the service is not available. After the recommended service is provided, the government department of first contact can seek reimbursement from another department/government.

- While Jordan's Principle can apply to jurisdictional disputes between governments (i.e., between federal, provincial or territorial governments) and to jurisdictional disputes between departments within the same government, a dispute amongst government departments or between governments is not a necessary requirement for the application of Jordan's Principle."Footnote 3

Jordan's Principle is designed to ensure that First Nations children, regardless of on- or off-reserve status, receive equitable treatment and access to government funded services. Some of the service areas funded under Jordan's Principle include:

- mental health;

- dental care;

- special education;

- physical therapy;

- speech therapy;

- medical equipment; and

- physiotherapy.

Jordan's Principle aims to implement the services and support to assist children with complex medical conditions, as well as their families. This ranges from mobility devices for children with health conditions to mental health/wellness programs designed to address mental health issues among First Nations youth. In addition to providing supports to children, a number of projects funded under Jordan's Principle also provide counselling and case management supports to parents or caregivers.

1.3 Jordan's Principle Implementation

The implementation of Jordan's Principle included a $382 million dollar commitment over three years (2016-2019) on behalf of the Government of Canada to enable:

- Service Coordination: Fund external organizations in order to provide supports where identified (gaps);

- Service Access Resolution Fund: Allocation of funds for Health Canada and Indigenous Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) to meet identified gaps;

- Data Collection: Collect and analyze service and financial data; and

- Capacity: Resources to ensure adequate human resource capacity regarding implementation.

Based on the CHRT's ruling, for most cases ISC is required to process requests for services within 12 to 48 hours. The timeframes for processing requests are outlined below.

Requests for a child or children in the same family or with the same guardian:

- Urgent requests (the child's current health or safety is a concern) are processed within 12 hours of receiving all necessary information; and

- All other requests are processed within 48 hours of receiving all necessary information if we do not have enough information to confirm the type of product, service or support the child needs, more time may be necessary to get this information; however, if the child requires an assessment of their need(s), this can be paid for immediately under Jordan's Principle.

Requests for a group of children from multiple families or guardians:

- Urgent requests are processed within 48 hours of receiving all necessary information; and

- All other requests are processed within one week of receiving all necessary information.

Requests that are approved under Jordan's Principle are managed by ISC in one of two ways:

- Where possible, ISC arrange for the products, services or supports to be provided directly to the child, or children. In these situations, there is no cost to the family, guardian, child or authorized representative and reimbursement is arranged directly with the service provider or vendor.

- If the family, guardian, child or authorized representative has already paid for the approved product, service or support, then reimbursement of these expenses is provided.Footnote 4

From the Jordan's Principle Government of Canada website, it is indicated that more than 165,000 requestsFootnote 5 had been approved by the federal government during the period from 2016 to September 2018. Furthermore, information supplied by Health Canada suggests that the approval rate for such requests was very high – at approximately 99 percent approval.

2. Scope of Work

2.1 Overview

For the purposes of this Review, case studies were selected with respect to the services coordination component, which included funding to specific projects designed to assist children/families. As part of the Review, interviews and focus groups were also held with parents to discuss how they had accessed Jordan's Principle funding and the impacts of such funding for themselves and their children.

As noted previously, R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd. was contracted to complete a review of Jordan's Principle, which included examination of some program documentation (when available), but primarily relied on a case study methodology, which included site visits to five (5) funded projects in three jurisdictions across Canada (Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan). The case study locations were identified by ISC although the specific projects assessed were developed in consultation with the project sponsors.

It should be emphasized that this Review was completed in a very compressed timeframe. The project was approved in July 2018, and site visits occurred in August to September 2018. Analysis and reporting took place in October to November 2018. The Review was also hampered by limited program documentation, and there was no program administrative data tracking either outputs or outcomes. Nevertheless, the results should be viewed with confidence given the in-depth approach taken with respect to the completion of each case study as well as the commonality of findings observed as part of this Review.

2.2 Purpose

The purpose of the Review was to assess the high level implementation of projects funded under Jordan's Principle, and to identify challenges and successes and, where appropriate, highlight outcomes achieved in the selected case studies.

In completing this Review, the research was guided by the following objectives, including to:

- Assess best practices;

- Include lessons learned; and

- Identify service delivery approaches that could be generalized.

In order to gain a broad understanding of the impact of project funding under Jordan's Principle, there were a diverse set of sites selected for the case study review. The models selected included expansion of pre-existing programs, sites which introduced entirely new programs/services, as well as projects which provided services on a province-wide basis. The actual sites visited are described in greater detail in Section 4 of this report.

The research activities completed as part of this Review included an examination of documentation, as well as interviews/focus groups with program staff, service partners, stakeholders and parents. As noted previously, while the focus of the Review was to assess "projects" funded under the service coordination initiative, the research team also collected considerable data pertaining to parental experiences with Jordan's Principle in terms of receipt of funding to support themselves or their children (i.e. respite, assistive devices, other). Additional information as to the specific research activities completed can be found in Section 5 of this report (Methodology).

3. Case Studies Issues and Questions

The Review of Jordan's Principle was designed to provide insights on a number of key issues and questions. These issues include:

- What is the overall context in which the delivery models are operating (in relation to Jordan's Principle)?

- How are these models being implemented?

- What gaps in service delivery need to be addressed?

- What are the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders and partners, and how do they work together?

- In what way is service delivery similar or different among the models?

- What has changed under Jordan's Principle?

- To what extent has Jordan's Principle contributed to the creation/improvement of partnerships, processes and service coordination through these initiatives?

- What are some key strengths and challenges, and what lessons learned can be taken to inform the longer term planning process?

- What are the resource requirements for each model? [not addressed in this report]

- What data collection tools and mechanisms are in place to support the identification and reporting, monitoring of services, both new and existing? [not addressed in this report]

It should be noted that due to the research methods used (case studies) and the limited availability of data; it was not possible to provide answers or insights to the last two research issues (resource requirements, data collection and monitoring tools).

4. Selected Case Studies

As noted previously, the case studies identified for inclusion in this Review were selected on the basis of different criteria. While two of the three case studies represented the "extension" of existing programming, one of the case study initiatives reflected the experiences of entirely new projects. Furthermore, the inclusion of the Early Childhood Intervention Program (ECIP) in Saskatchewan provided some insights as to funding for a province wide initiative. Additional details for each case study are provided below. In addition, detailed findings for each of the three case studies are included in the appendices to this report.

4.1 My Child, My Heart (Manitoba)

The My Child, My Heart case study (see Appendix A) represents funding provided for a pre-existing program that received funding to support continuation and enhancement of the programming. The program was initiated in 2015 as a pilot project. The project is located in the Pinaymootang First Nation in northern Manitoba. The project includes intensive case management services provided to children aged 0-21 irrespective of on/off‑reserve status, as well as their families as needed.

The two core goals of the My Child, My Heart project were as follows:

- Service provision for children; and

- Development of practice standards and guidelines for First Nations implementation of Jordan's Principle in Manitoba.

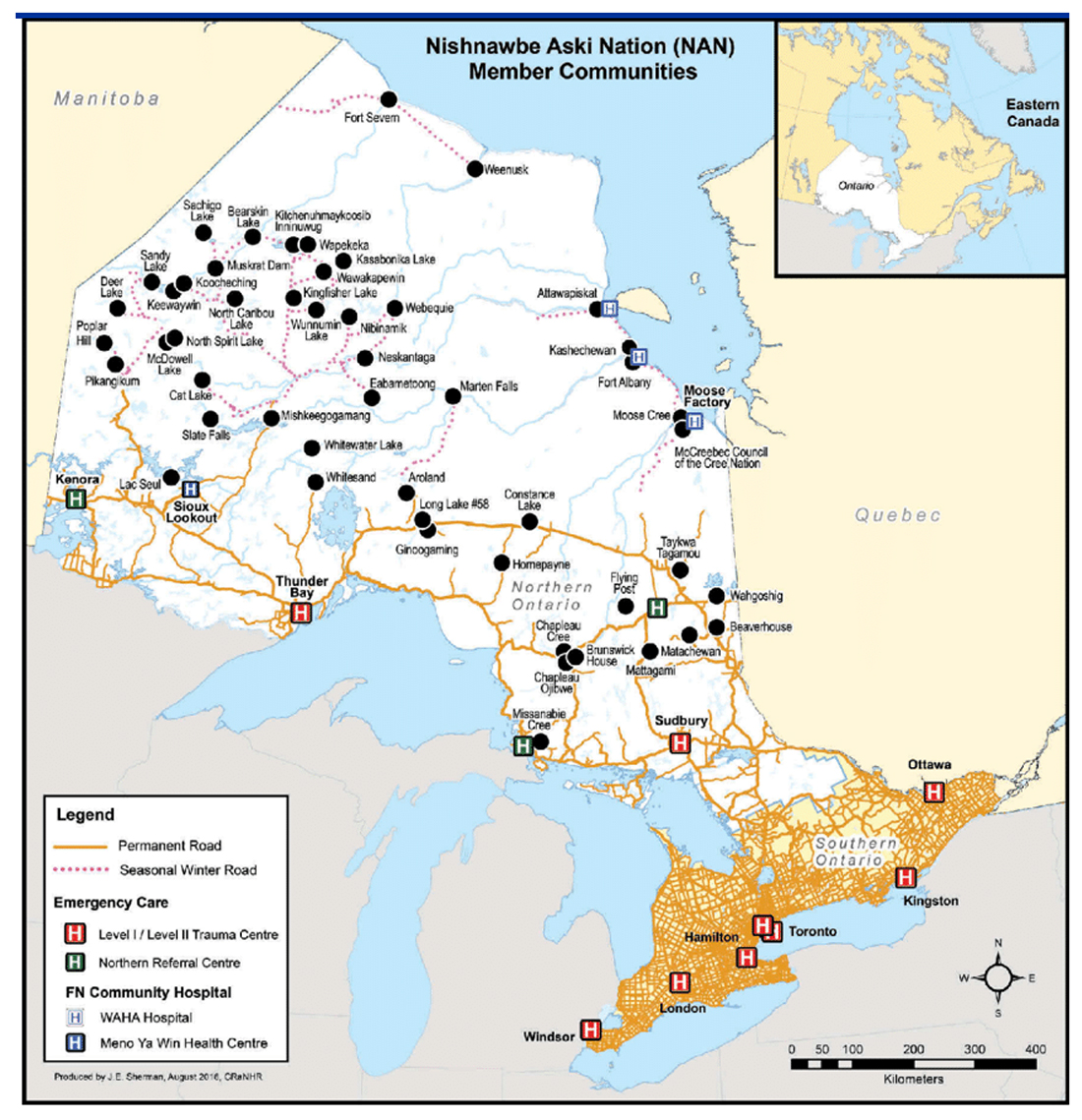

4.2 Choose Life (North Western Ontario, Three Projects)

The Choose Life case study (see Appendix B) represents funding provided to projects that did not exist prior to Jordan's Principle. In the case of Choose Life, three projects were selected for Review out of more than 122 Choose Life projects that had been funded under Jordan's Principle in the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN). Many of these projects were designed to address mental health and youth resilience issues, as the region had experienced a high rate of youth suicides in the past. Many of the projects included funding for land-based programs that served to build youth self‑esteem, cultural affiliation and self-worth.

In discussion with the Choose Life co-ordinators, it was noted that many of the projects were "new", and were only funded in fiscal year 2016-17 or fiscal year 2017-18 with funding ending in March 2019. As noted previously, the selected projects were designed to address youth mental health/crisis issues.

As part of the case study, three projects were examined including:

- Keewaytinook Okimakanak Secondary School Services (KOSSS) - Thunder Bay;

- KOSSS – Sioux Lookout (Home Support Workers); and

- Lac Seul (Land Based Program).

4.3 Early Childhood Intervention Program (Regina Saskatchewan)

The ECIP (see Appendix C) was established in Saskatchewan in 1980 to provide services to children with developmental delays (i.e. genetic, environmental, medical etc.). ECIPs are primarily funded by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, although ECIPs typically receive additional funding. In Saskatchewan, ECIPs had received funding from various federal departments (Health Canada, First Nation and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), INAC, ISC) to provide services to on-reserve First Nation youth aged 0-6. However, under Jordan's Principle, ECIPs in Saskatchewan applied and received funding to expand services to include First Nation youth (both on- and off‑reserve) aged 6 to 17 (and in some cases aged 21).

The core services provided by ECIPs include the following:

- Family Support (via Jordan's Principle application support);

- Case Coordination and Transition Support;

- Community Development and Partnerships; and

- Referrals.

It should be noted that while ECIPs generally provide the same services, the focus of the case study was the Regina ECIP, although data was collected as to the program activities undertaken in two other ECIPs (Children North – La Ronge, and Northeast) as part of Jordan's Principle funding.

5. Methodology

5.1 Methods

The Review included an examination of documentation provided by ISC, online review of the programs/services offered in each case study community, and a site visit to the program delivery location.

In advance of each site visit, a community site visit profile was developed. The profile provided important background information about the community as well as the programs/services that were available in each community.

Staff from Malatest arranged visits to each community. Generally, each case study included three days "onsite" as well as time to travel to/from the location. In coordinating visits to each community, it was mentioned that the research team would like to meet with program staff, service providers, other stakeholders and parents as appropriate.

The sites visited and data collection that occurred is detailed in Table 1.

| Site/Activity | My Child, My Heart | Choose Life | ECIP Regina |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community | Pinaymootang First Nation, Manitoba |

|

Regina, Saskatchewan |

| Dates | Aug 20-22, 2018 | Sep 19-21, 2018 | Sep 24-26, 2018 |

| Consultations |

Program Staff/ coordinator (4) |

Thunder Bay – NAN

Thunder Bay – KOSSS

Sioux Lookout – KOSSS

Lac Seul

|

ECIP Coordinators (3)

ECIP Regina staff (4)

|

5.2 Research limitations

It should be noted that this Review had several limitations. These limitations include:

- Short timelines: The Review was completed on a short timeline. The project started in July 2018, site visits occurred in August to September 2018, and final reporting occurred in October to November 2018. As a result of this compressed schedule, it was not possible to conduct an in-depth examination of administrative data (which was not available), nor was it possible to obtain additional data about the sites. Scheduling issues also limited the extent to which staff, other stakeholders and parents could participate in the study.

- Limited access to reports/documentation: While the research team was provided with limited documentation for the selected case study projects, there were other important documents that were not provided to the team. Among these included the annual reports submitted by each project that would have provided additional information as to services provided and children served.

- Qualitative focus: Case studies by definition tend to provide detailed contextual information, however, findings from case studies are difficult to "generalize" to all projects. This is problematic in terms of estimating the cost of service provisions as well as other indicators such as child development, school transition, and/or other metrics associated with improved child/family well-being.

- Possible Selection Bias: It should be noted that the project coordinators selected/identified the appropriate staff, stakeholders and parents who were interviewed as part of this Review. In this context, it is possible that individuals selected were purposely chosen for their positive support of the program.

6. Key Findings

Key findings in this section are presented under the key research questions as previously described in Section 3 of this report. Findings have been generalized across the various case study sites visited and represent the Research Team's interpretation of findings.

6.1 What is the overall context in which the delivery models are operating (in relation to Jordan's Principle)?

Overall, it was found that projects that had existing infrastructure or were extensions of existing projects (My Child, My Heart, ECIP Regina) experienced fewer implementation challenges than did "new" projects (Choose Life projects).

In general, it was found that the new projects lacked:

- Understanding of program design process;

- Understanding of how to link program activities with desired outcomes;

- Understanding of appropriate assessment and intake procedures in mental health;

- Availability of qualified and trained staff in the community;

- Time to develop relationships with other community service providers;

- Development of case management models;

- Community isolation impacts resource availability; and

- Two year funding window was insufficient for program design and implementation.

In addition, it was found that in the more isolated communities, there was a general lack of clinical and professional supports (mental health workers, other health professionals) that impeded the ability of projects to deliver programs and services. Furthermore, project stakeholders noted that the two year funding window for new projects did not allow for sufficient time to design, implement and modify programs to meet community and client needs.

It is important to acknowledge that given the CHRT's ruling that applications be processed within 12 to 48 hours and that service gaps be quickly addressed by the federal government, it is not unexpected that new projects that did not have pre-existing health services infrastructure would also not have comprehensive design and delivery approaches. It is expected that with funding stability, new projects and programs would have more time and capacity to develop their approaches and this would help ensure a smoother roll-out and implementation.

6.2 How are these models being implemented?

As noted previously, for those programs/projects in which there was a pre-existing program or infrastructure, program roll-out and implementation proceeded much more smoothly than was the case in projects that were being developed "from scratch".

In general, project coordinators noted that they did spend time talking to other stakeholders and First Nation communities about the proposed program/project, but the level of consultation varied on a project by project basis.

For newly designed projects or programs (i.e. Choose Life), it was found that program implementation lacked proper program design and implementation structures. For example, due to the tight funding window, it was noted that there was limited or no time to undertake a community analysis, do proper "gap identification" and develop a proper service plan. For new programs, such programs were often introduced without a program logic model (relating how inputs and activates would support desired outcomes), nor were community service maps generally developed (that would identify who could provide what services in each community). Furthermore, new programs were generally launched in their entirety, but could have benefitted from an approach that made use of pilots and/or phased implementation.

Program coordinators also noted that they received very little support or guidance from Health Canada. While Health Canada staff did work with the program coordinators to help ensure that submitted application would eventually result in a funded project (particularly in Choose Life), they offered little assistance in terms of providing advice/guidance as to the steps that should be taken to introduce new health programming at the community level. As noted, given the rapid roll‑out of programming to meet the CHRT requirements, in many cases, there was likely not enough time to provide sufficient support for new programming.

This was a classic "learn as you go approach"; I wish that someone could have given us more direction or help in terms of setting up this program and making us aware of what "we did not know"

6.3 What gaps in service delivery need to be addressed?

Across the various sites visited, a common theme that emerged was the desire to see programming for youth extended beyond the current guidelines of 0 to 17 years of age. As one stakeholder noted:

The issues faced by an individual do not disappear when they turn 18 years of age.

While some projects did make allowances to provide supports to individuals up to the age of 21, it was felt that more guidance/funding should be provided to either support older individuals (to age 24 or even age 29), or provide transitional supports to such individuals. In addition, it was noted that some individuals had already "aged out" of Jordan's Principle funding having spent their entire youth without appropriate supports and services.

While both program staff and stakeholders noted that the Jordan's Principle funding had allowed for the provision of programs and services, not all children/families were actually receiving required services. This did not reflect a program issue, but rather, difficulty in securing appropriate qualified staff in rural/remote regions (Psychiatrists, Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs), and Occupational Therapists etc.). Additionally, with My Child, My Heart, program staff acknowledged that it takes time for children with developmental delays to be identified and for the parents to then accept that their child requires additional supports.

6.4 What are the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders and partners, and how do they work together?

As part of Jordan's Principle, the degree to which project sponsors engaged in community/service partner outreach to identify program gaps and possible service delivery options varied. Existing programs appeared more aware of other service providers and had more formalized approaches to case management. In new programs, stakeholders and project proponents noted that such consultations did occur, however, it appears that consultations were not comprehensive nor did they formally involve all service partners, in program design/administration.

Thus for new programs, it did not appear that the roles/responsibilities of all service partners were identified and documented. While relationships existed between the project and some primary partners (i.e. KOSSS Sioux Lookout and local school board), program design was not based on an extensive consultation with all stakeholders and/or service partners. For example, there was no evidence of comprehensive service coordination given that the projects visited did not developed a "community service map" (i.e. identify what social/health services already existed in the community), nor was there evidence of agreements (Memoranda of Understanding, other) between the funded projects and other service coordinators. In fact, in the ECIP case study, it was noted that Health Canada may have actually funded two very similar projects in the same community (i.e. ECIP was funded to hire Speech Language Pathologist to provide services to on-/off‑reserve First Nation youth, and a nearby First Nation Band was also provided funding to hire a Speech Language Pathologist to provide services to some of the same children).

It was noted that consultation and communication did occur between the funded projects and other stakeholders, but such consultation was generally initiated by project staff during informal case management, rather than as part of a formal communication/outreach strategy.

6.5 In what way is service delivery similar or different among the models?

As noted previously, each of the five projects reviewed had considerable variation in program consultation, design, implementation and execution. While some projects (My Child, My Heart, ECIP) had a distinct dual focus in terms of supporting both the child and parents, other projects (Choose Life) seemed to be primarily focussed on providing services to children and youth.

Detailed in Table 2 is the program focus for the three case studies reviewed as part of this study.

| My Child/My Heart | Choose Life | Regina ECIP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced case management | Yes | emerging | Yes |

| Introduction of new projects/activities | Yes | Yes | limited |

| Focus on parental supports | Yes | limited | Yes |

| Use of new staff/processes | Yes | Yes | Some new staff |

| Use of existing staff/support services | Yes | Yes Some new staff |

In terms of "functionality" of the projects, for the case studies conducted on projects that existed prior to receipt of Jordan's Principle funding, these projects tended to be able to roll-out services much more quickly than was the case for new projects. It was also observed that program management, case file administration and program activities varied on a site by site basis. This again reflects the fact that Health Canada did not prescribe (nor provide) program "tool kits" that would identify key program elements, reporting structures and/or consultation requirements. It should be noted however, that all programs collected some data and were interested to collecting the correct data to demonstrate outcomes, but were often unclear on what data was most appropriate.

6.6 What has changed under Jordan's Principle?

In discussions with program staff, stakeholders and parents, it appears that Jordan's Principle funding is generating a range of positive outcomes that are enhancing the health and quality of life for both youth and their parents.

Case study participants identified a range of outcomes associated with programs/services now available via Jordan's Principle. Among these include:

- Reduction in suicides/suicide attempts/other incidents;

- Improved cognitive and social functioning;

- Extension of services from children to youth;

- Improvement in school attendance and academic achievement;

- Increased ability for families to remain on‑reserve; and

- Improved environment for parents.

In addition to the impacts identified by program staff/stakeholders, parents who were interviewed as part of this Review were also very supportive of the program. Parents cited a number of benefits of the program (either via the funded project, or via direct application to Jordan's Principle to obtain financial support for services/other). The benefits/impacts identified by parents are summarized as follows:

- Active "champion" for family: Projects that included funding for enhanced case management (My Child, My Heart, ECIP Regina) generally included a "wrap around" case management approach in which the case managers would work with the child/family to obtain necessary support either under Jordan's Principle or from other community/social service agencies. This active support was seen as a very positive step in terms of assisting First Nation families navigating a complex service environment for children with various health conditions. Almost all parents talked about being better "able to parent" because of the supports provided by the case management worker as well as the Jordan's Principle funding for required supports/services. Parents were also very positive about the support they received from case managers who would identify what services/supports that they should apply for, assist such parents in applications, and generally serve as an advocate in their interactions with other education, health and social service agencies.

This program is a Godsend…we finally feel that we have someone on our side helping to make sure our daughter has access to the supports she needs..instead of fighting us, they are helping us.

The other major ways in which the Initiative had supported families included:

- Positive child outcomes from provided supports: Parents identified that receipt of funding for respite as well as other supports (i.e. adaptive technologies, home adaptation, other) were having a number of positive outcomes. Thus, parents for example noted that their child: could now attend school, could return to their care, communicate their needs, had a group of friends, were more readily accepted in the community, stayed in school, and demonstrated more positive coping mechanisms and behaviours. Parents also noted that the respite funding allowed them to find caregivers to take care of their children, many indicated that in the absence of such funding, they would have to consider temporarily "signing over" their children to a social service agency in order to get some relief from the 24/7 demands of their child with complex medical needs. Parents were also very positive in terms of other supports now available to them under Jordan's Principle, such as funding for child assessments, tutoring, learning technologies (iPads and learning/communication software) as well as funding for direct service provision (SLPs, OTs, other).

- Improved education outcomes: Parents and stakeholders interviewed as part of this research noted that the children who were now being supported via the Jordan's Principle funding were benefitting from such supports. Parents and stakeholders cited such improvements as increased school attendance, improved academic scores (due to tutoring and other supports) and access to additional educational supports given that some student assessments were "fast tracked" due to the ability of using Jordan's Principle funding to obtain such assessments.

It should be noted that it appears that Health Canada has yet to establish a reporting framework that moves beyond reporting on financial expenditures and activities (i.e. numbers of children served). While the research team was not supplied with the annual reports submitted by the projects to Health Canada, it was noted that such reports did not ask the project proponents to identify the "impacts" or outcomes associated with such funding. While stakeholders were in agreement that their projects were having a positive impact, they noted that they did not currently track such outcomes as this information was not requested by Health Canada or they were uncertain about what should be tracked and how.

6.7 To what extent has Jordan's Principle contributed to the creation/improvement of partnerships, processes and service coordination through these initiatives?

Stakeholders noted that as part of their program roll-out, they would undertake consultations with communities and service providers as to program objectives and elements. As noted previously, it does not appear that programs were designed in a stepwise manner (i.e. where one would expect to see funding for program coordination and consultation, funding for program design, and funding for program implementation). Coordination of services was likely improved under Jordan's Principle, but for the projects that were visited, the research team could not observe a high degree of service coordination (although relationships certainly exist with referral agencies). Programs were all aware of the concept of case management, but were in different stages of implementing case management approaches for the children and youth they serviced. As the case management approaches were formalized, programs expected that greater service coordination would occur. Programs with the greatest service coordination had existing service partnerships or relationships in place prior to the initiative funding.

As noted previously, while it appears that service coordination likely improved, it is likely due to the work done at the staff level (i.e. case managers consulting with other service providers), rather than at the program level. The Research Team did not see evidence of formal structures that would indicate a high degree of service coordination (re: no community service asset map, no inter-agency Memoranda of Understanding, other) although given the few sites visited, this may not be indicative of all projects/programs funded under Jordan's Principle.

7. What are the Key Strengths and Challenges, and what are the Lessons Learned?

7.1 Key Strengths and Challenges

As noted throughout this report, Jordan's Principle funding has resulted in a number of positive outcomes and reflects a new process in which programs/services can be provided to First Nation youth (and their families) with complex medical conditions. However, the very rapid roll-out of the program, with very limited support resulted in considerable challenges for projects that were "new" and did not benefit from pre-existing structures, staff and/or relationships with other service partners. Based on the three case studies completed, the strength and challenges of Jordan's Principle funding is summarized in Table 3.

| Strengths | Challenges |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.2 Lessons Learned

Highlighted are the key lessons learned from the Review of Jordan's Principle. As noted earlier, given the very limited lines of evidence used in this Review, these "lessons learned" must be interpreted with caution.

Project or program effectiveness varies considerably on the basis of prior program history

The results of the Review suggest that program implementation (and ultimately program effectiveness) is highly correlated with the prior history of the project or program. For example, from the case studies, programs that were in operation prior to Jordan's Principle funding (My Child, My Heart, ECIPs) were much better able to launch "new" programs/services as they had existing program administration, management structures and relationships in place. In contrast, projects that were only just started as a result of Jordan's Principle (Choose Life) experienced significant challenges in terms of program design, implementation and service delivery.

Need for clear program theory underpinning programming actives

As noted previously, some programs were unclear if the activities they were completing clearly linked to the outcomes they were seeking (i.e. positive mental health outcomes). Good program design requires sound theories of change that show the link between program activities and the desired program outcomes. Simply developing a robust program theory and implementing it could take two years. At the community level, communities did not have the capacity to complete such a task, and as noted, nor did the administrative organization. Time is required for the administrative organization to build this capacity prior to rolling out program funding. Thus program design funding is required prior to program funding.

It should be noted however, that given the CHRT's ruling that applications be reviewed within a 12 to 48 hour timeline, the challenges associated with program design/implementation reflect a desire to satisfy CHRT's vision of "quick" service delivery to meet unmet needs, as opposed to a more comprehensive approach that would likely have better addressed program design and implementation issues.

More guidance /support should be provided to newly developed programs funded under Jordan's Principle

It is clear that given the limited funding window, projects and programs were often "rushed" in order to meet financial targets. However, such an approach resulted in disjointed service delivery and ultimately, development of programs in isolation of broader community requirements. In the future, "new" project or programs funded under Jordan's Principle should be funded in a staged approach. These stages could include:

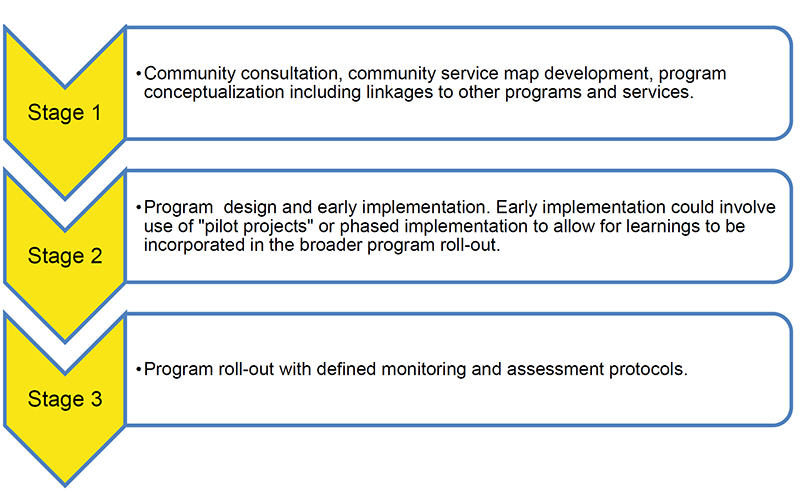

Figure 1

Text alternative for Figure 1

The figure depicts the three stages of Program Delivery.

The first, Stage 1, is described as "Community consultation, community service map development, program conceptualization including linkages to other programs and services."

The second, Stage 2, is described as "Program design and early implementation. Early implementation could involve use of "pilot projects" or phased implementation to allow for learnings to be incorporated in the broader program roll-out."

The final, Stage 3, is described as "Program roll-out with defined monitoring and assessment protocols."

Examples of supports that could have been developed by the administrative organization and made available at the community level would include:

- Workshops outlining Jordan's Principle;

- Workshops on application completion;

- Workshops and toolkits on program design;

- Workshops and toolkits on theories of change, logic models and program monitoring and measurement;

- Toolkits with commonly used program protocols such as intake forms and consent forms; and

- Workshops on Human Resources processes for hiring, contract development, etc.

Address Capacity and Infrastructure Challenges

Under Jordan's Principle funding, there was a desire to implement new programs and services, many of which required trained and qualified health professionals, as well as the need to hire significant numbers of staff to work in the programs/projects. It was clear that while Jordan's Principle resulted in the injection of considerable resources to meet community need, there were gaps/challenges in terms of having the available infrastructure (offices, space, other) and human resources (trained and qualified health staff, project coordinators, various support workers etc.) to effectively support the funded programs/projects. In this context, it would be important to not only provide funding to support programs, but a portion of the funding under Jordan's Principle could be earmarked for infrastructure and/or other capacity building at the community level.

Appendix A: My Child, My Heart Case Report

Niniijaanis Nide – My Child, My Heart Program

Program Review – Community Visit Summary

1. Community Background

Pinaymootang First Nation is part of Manitoba's Interlake Region, within Treaty 2 territory. The community is situated approximately 250 km north of Winnipeg along Highway 6 on Fairford 50 Reserve. The band has approximately 3,258 members: 1,271 living on‑reserve and 1,987 residing elsewhere.Footnote 6 As compared to the rest of Canada, the population of Pinaymootang First Nation is young, with 50 percent of its members under the age of 20.Footnote 7

Pinaymootang First Nation is a member of the Interlake Reserves Tribal Council Incorporated. Chief Garnet Woodhouse and Council were elected in October of 2017. The Nation began receiving Block Funding in 1998.

The community has a wide range of services, including a school, administration office, daycare, fire/police protection services, water plant, three community churches, employment and training facility, Child and Family Services, sewage/garbage disposal, postal services and health services.

The Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre provides health services with the aim of promoting healthy lifestyles and improving access to reduce health inequalities. The Niniijaanis Nide: My Child, My Heart Program, currently funded through Jordan's Principle, is housed within the Health Centre. The Health Centre employs 26 staff. The expanded Health Centre opened on July 4, 2018, and includes additional examination rooms, office spaces, as well as a kitchen and meeting/event room.

2. My Child, My Heart Program Overview

2.1 Program History

As a pilot program, My Child, My Heart (Integrated Approach to Services for Families with Children with Complex Needs) began operating in 2015, under Health Services Integration Funding, through collaboration between Pinaymootang Health Centre, Anishinaabe Child and Family Services, Pinaymootang School, Pinaymootang Social Program and Health Canada, First Nations Inuit Health Branch (Manitoba Region). The pilot ran from December 15, 2015, to March 31, 2017, under Health Services Integration Funding.

The pilot resulted from a complaint filed by a Pinaymootang family with the Canadian Human Rights Commission, which argued that their child's complex health care needs were not met by the services available in the community. Health Canada's subsequent request to the Pinaymootang Health Centre to submit a proposal to meet the needs of this child lead the centre to instead submit a proposal to meet the needs of 11 families of children with special health care needs thus fulfilling their role as health care advocate for the community.

From April 2017 to March 31, 2018, as well as in the current fiscal year (April 2018 to March 2019), My Child, My Heart was funded through Jordan's Principle.

2.2 Program Objectives

The goal of Niijaanis Nide: My Child, My Heart is to allow children to access services where their families and support networks are located and in a home setting where they feel comfortable and safe. My Child, My Heart has six key values: Footnote 8

- Children are best cared for at home and within families;

- Special needs of children and families have to be met as well as their basic needs;

- Parents know their child better than anyone else and must be treated respectfully;

- Professional supports must be coordinated and responsive to the needs of individual children and families;

- Identify risks to be managed in ways that provide safety and good quality of life to the child and family; and

- Partnership working across disciplines and agencies is essential.

My Child, My Heart supports children with complex needs in Pinaymootang from birth to 21 years of age. Children can live on- or off‑reserve. Children with complex health care needs are defined as children with a congenital or acquired long-term condition that are attributed to impairment of the brain and/or neuromuscular system that create functional limitations.

3. My Child, My Heart Program Operations

A Community Advisory Committee provides oversight to the program, with members representing health, education, and social programming.

3.1 Staff

The program includes:

- One Case Manager/Project Coordinator;

- One full-time equivalent (FTE) Nurse or Social Worker;

- Three to five FTE's Child Development Worker (CDW), Health Care Aids or Early Childhood Educators (ECE's);

- Ten part-time respite workers for evening and weekend family respite; and

- One Administrative Assistant/data entry position.

3.2 Services

A wide range of activities are carried out by the program:

- Provide evening and weekend respite care for families;

- Collaborate with service providers;

- Advocate for continuum of care for children with complex needs;

- Provide a continuum of family training;

- Build partnerships across disciplines and agencies within the community that provide services to the children with complex needs;

- Provide staff education and training related to caring for children with complex needs;

- Provide day and evening programming for children with complex needs; and

- Provide one-on-one work between the CDW and the child.

Many of the services are provided in the Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre. The addition of the kitchen and meeting room in July 2018 has enabled the program to hold day and evening programs for children and families.

The program has developed a program delivery process aimed at providing continuous, integrated care to children with complex needs so as to allow them to remain living in Pinaymootang. The five phase program delivery process is as followsFootnote 9:

- Phase 1: Establishing a relationship:

- Meet with the child and parent to allow them to share the child's strengths, challenges and preferences. The phase allows workers to get to know the family and child and establish trust.

- Phase 2: Identifying needs and objectives:

- Identify what the parents want for their child.

- Develop one to three objectives with the CDW.

- For each objective, develop benchmarks for goal attainment and scales to measure attainment of goals.

- Phase 3: Implementing the program:

- The CDW implements the program based on the goals and objectives identified in Phase 2.

- There are two components to program implementation:

- Basic Care and Support (e.g. occupational therapy (OT) and physical therapy (PT)); and

- Goal-Oriented Work (e.g. behavioural goals).

- Phase 4: Generalizing Goals:

- The CDW works with the child, family and others to ensure objectives are generalized across different people and different settings using a variety of materials and tools.

- The CDW support and coach the parents/caregivers and train any secondary caregiver.

- Services are provided in different environments (home or school) using a variety of resources.

- Phase 5: Conducting evaluation and providing continuing care support needs:

- Provide support to parents and caregivers and evaluate continuing basic care and support needs.

- The following are evaluated:

- Child-oriented goals; and

- Family-oriented goals; (stress and coping mechanisms);

3.3 Case Management

Once a child's service plan is developed the program holds regular case management meetings with the necessary service providers to discuss implementation, provision and generalization of services for each child. The families are included in the case management meetings. Case management is critical to continuity of care and ensures that teaching and services are reinforced and provided across a wide range of environments including the home, school and community. All service providers interviewed stressed the importance of the case management meetings and noted that the program has successfully leveraged the case management model in part due to the strong partnerships that the program has established.

3.4 Partnerships and Service Providers

The program has established a number of partnerships or working relationships which allow the provision of services to children with complex needs within the community. While in the pilot phase My Child, My Heart began working with several partners to provide services to the 11 families. The range of partnerships has since expanded with the introduction of funding through Jordan's Principle. In the case of the Rehabilitation Centre for Children, the St. Amant Centre, and the Manitoba Adolescent Treatment Centre, the services partners, at the request of ISC (formally (INAC), have established contractual preferred service provider relationships that allows provision of services to children with complex needs on any reserve across Manitoba. These contracts were developed through a proposal-based procurement process and are funded by Jordan's Principle.

Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre: the centre provides significant in-kind contributions to the program, including office space for their staff, program space and program oversight (the salary of the Health Director is entirely covered by other funding although they are involved in program oversight). Additionally, the centre is accredited which helps to ensure the overall quality of all services provided to children with complex health care needs within the centre.

Pinaymootang School: representatives of the school sit on the Community Advisory Committee and attend the case management meetings as needed. The school works with the program to coordinate services provided to children in school by Special Educational Assistants and CDWs. Support to children with complex needs while in school is funded through the school budget. Since the implementation of the program, the school has noted improved attendance among children with complex health needs, as well as improved integration and inclusion by other children. School representatives were unable to speak to improved academic performance. The school is currently not concerned about being able to meet the needs of children with complex health care needs during school hours.

Pinaymootang Daycare: the program works with the staff of the daycare to identify children potentially in need of services. The daycare refers families to the program if it is believed that special services may be required.

Anishinaabe Child and Family Services: coordinates services provided through the agency and My Child, My Heart, including in-home care services, during case management meetings.

Rehabilitation Centre for Children: provides OT, PT and speech therapy to children in the program. Given the Centres' more recent involvement in the program roles, responsibilities and communication lines are still being established between the Rehabilitation Centre for Children, the program and other service providers. High levels of investment from My Child, My Heart case managers have supported the introduction of services from the Rehabilitation Centre for Children to date. As well as providing OT, PT and speech therapy to children in the program, the Rehabilitation Centre for Children has completed training with program staff, and provided developmental checklists to community service providers to assist them in identifying children that should be referred to the My Child, My Heart program. Additionally, the Rehabilitation Centre for Children has developed and provided to the program a brochure explaining the services they provide for distribution among families. Representatives from the Rehabilitation Centre for Children noted that the program had resulted in developmental delays among community children being caught and treated earlier. Further, interviewees noted that necessary equipment that was not covered through Non-Insured Health Benefits has been provided through My Child, My Heart program funding.

St. Amant Centre: a basket of services are available to the My Child, My Heart program children and families through the St. Amant Centre including: non-crisis counselling for parents, siblings and the child, the family care program (advocacy and navigation), dietician services (dealing with challenging eating), and counselling for dealing with challenging behaviour in children with complex health care needs. Uptake of the St. Amant Centre services has been high among program families. As with other newer service providers, the St. Amant Centre works directly with the program case management team to coordinate and deliver services. The centre has also provided training to school staff to better support the children in the program. The centre noted improved family dynamics in the home, reduced difficult behaviours among the children, and increased positive behaviours in children (e.g. using the toilet, traveling in a vehicle, and return to school). The center is still working to establish an appropriate caseload for their staff but have needed to hire additional staff to meet demand for services from this program and other programs across Manitoba. A significant outcome noted by interviewees from the centre was the reunification of one child with their family and the planned reunification of another. In both cases, the children could now return to Pinaymootang where services are available rather than staying in a special care facility to have their needs met. Interviewees also noted that parents previously considering putting their child in a full-time care facility were no longer considering this option.

Manitoba Adolescent Treatment Centre: has worked with the My Child, My Heart program for four years providing mental health and psychiatric services, including preliminary assessments, arranging initial consultations for diagnosis, and ensuring medication is obtained. The centre provides mental health supports to youth, their families, and will consult with other service providers and the school. Consultations with psychiatrists and counsellors are completed through Tele-Health at the Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre; in-person consultations can be scheduled if the doctor feels it is needed. After diagnosis, ongoing monitoring and prescription renewal is completed by community-based physicians that visit the Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre. Barriers to service access noted by the interviewee included access to Manitoba Tele-Health, which is in high demand. Additionally, the central location of the Tele-Health equipment reduces privacy and can introduce confidentiality concerns. Clinicians stay in direct contact with the child's CDW to support case management as required. The Manitoba Adolescent Treatment Centre is still working with the service providers within My Child, My Heart to define roles, responsibilities and lines of communication on a case-by-case basis. Regular meetings among service provider management were said to be helping to support collaboration and the establishment of clear roles and responsibilities. The most significant challenges noted by the interviewee to the provision of services is the availability of on-the-ground support for individuals who are a threat to themselves or others. While this was not noted as a concern in the My Child, My Heart program, it has been noted in more remote programs in isolated communities.

Eagle Urban Treatment Centre: the My Child, My Heart program provides families referrals to the Eagle Urban Treatment Centre when they are leaving Pinaymootang to relocate elsewhere in Manitoba. Conversely, the centre notifies the program when a family is returning to the community to ensure continuity of services. Within Manitoba communities, the Eagle Urban Treatment Centre provides advocacy and referral to families. Advocacy was said to be important to support families navigating the provincial system to ensure children with complex health needs receive the required services under Jordan's Principle.

3.5 Program Outreach

The program received referrals from service providers as well as services in the community (school, daycare, etc.). Additionally, the program advertised available services through various methods including booths during community events.

3.6 Scope of Service Provision

Currently, My Child, My Heart provides services to approximately 60 children, many of whom receive ongoing support. Of the 60 children, 15 are currently transitioning to school, 12 received support services and 33 are actively involved in the program. Examples of the types of services provided included:

- Day program activities (reading club, physical activity night, "nagamon" music club, Moe the Mouse-read);

- Parent support meetings;

- Parent and caregiver classes;

- American Sign Language training for two families;

- Physiotherapy and occupational therapy;

- Speech and language therapy and audiology therapy;

- Visual therapy;

- Dietician services;

- Behavioural/cognitive behavioural therapy;

- Psychologist and psychiatrist consultations, spiritual wellness supports, and mental health therapy;

- Child development supports (individual);

- Home modifications;

- Home visits for extended families; and

- Respite care.

3.7 Program Budget

The annual budget for the My Child, My Heart program during the years it was funded through Jordan's Principle is shown in the Table 4. Across both years, the budget has remained the same, with it costing approximately $12,660 per child (60 children) to provide service. In addition to the core budget, the program received one-time funding for a handibus ($78,864.32) and American Sign Language Training (training: $7,800 plus facilitator travel: $1,560). In should be noted that the Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre provides in-kind resources (facility space and utilities), which would need to be covered under the project budget if this facility was not available.

| Program Expenses | Annual Budget | |

|---|---|---|

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

| Case Manager/Project Coordinator (One FTE Nurse or Social Worker) | $75,000 | $75,000 |

| CDW, Health Care Aids, or ECE's (Three FTEs; $39,000 each) | $117,000 | $117,000 |

| Ten part-time respite workers for evening and weekend family respite ($27,000 each) | $270,000 | $270,000 |

| Administrative Assistant/data entry position | $35,000 | $35,000 |

| Employee Benefits (14 percent) | $69,580 | $69,580 |

| Total Staff | $566,580 | $566,580 |

| Staff Training/Professional Development | $36,000 | $36,000 |

| Travel | $28,000 | $28,000 |

| Program Activities | $60,000 | $60,000 |

| Sub Total | $690,580 | $690,580 |

| Admin Fee's (10 percent) | $69,058 | $69,058 |

| Grand Total | $759,638 | $759,638 |

3.8 Monitoring of Child and Family Outcomes

The program monitors child and family outcomes at three, six, nine and 12-months post-intake. A goal attainment scale is used to determine if the family has been able to meet the goals they set for their child. Standardized tests used by the program include the:

- Measure of Processes of Care (20-item measure on parents' perception and satisfaction of the services provided for their child);

- Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (36-item measure tool that documents levels of stress – whether or not families are feeling supported);

- Social Support Index (17-item measure that taps into parents' experience of their support networks both with and outside the family); and

- Family Quality of Life (25-item measure that evaluates family quality of life, through five domains):

- Family Interaction;

- Parenting;

- Emotional Well-Being;

- Physical/Mental Well Being and;

- Disability Related Supports.

3.9 Program Outcomes

In 2016, the Canadian Home Care Association published a report on the impacts of the My Child, My Heart program. Among children, increased independence, socialization and sense of accomplishment were all observed. This was accompanied by a decrease in problematic behaviours. As a result of their interaction with the program, parents and caregivers were said to have increased connection with their child, trust in the health system, feelings of competency, coping, connection with other parents and ability to actively participate in the child's care.

Service providers were unanimous in their agreement that without My Child, My Heart, children with complex health needs living on Pinaymootang First Nation Reserve would be unable to access the necessary services required to meet their needs. Without such services these children were less likely to attend school, remained socially-isolated, and were unable to reach their potential. Further, many families would be unable to remain in the community if these supports were not available.

Parents who attended the focus group all felt that they had received the supports they required for their children through the program. Parents were unable to list gaps in supports and felt that the available services were meeting their child's immediate and long-term needs. Parents noted that their children's behaviour was more manageable and their children were less socially-isolated. Respite care was appreciated, as was the ability to share stories with other parents. Parents noted that they felt less isolated and that the program had helped take away feelings of self‑doubt or blame that their child's development or behavioural challenges were their fault. Some of the children had returned to school or began attending school for the first time as a result of the support. Many parents stressed that without the program they would need to move to Winnipeg to ensure their child's needs were met; however, in doing so, they would be left without social, emotional and respite support from friends and family.

3.10 Program Challenges

Given the length of time the program had been operating and strong program leadership, the My Child, My Heart program was experiencing few challenges. Program staff, however, estimated that they had been unable to reach all children with complex health needs who required support within the community; in part due to the reluctance of parents to have their children assessed. Program leaders also acknowledged that many families with high needs children had relocated to urban centres to assess provincial supports and had not yet decided to return to the community now that on-reserve supports had increased. It was expected that demand for services would increase as families displaced during the 2011 flood began moving home. The expansion of the Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre had resolved the program's facility challenges, as there was now sufficient space for program staff and programming activities. Staffing was also not a challenge for the program as individuals with the necessary skills reside in the community.

The most significant challenges highlighted by stakeholders interviewed were:

- Uncertainty of funding; and

- Lack of funding for individuals aged 22 and older.

Without long-term funding, the program is less able to plan and retain staff. The uncertainty of funding also impacts families who were unclear what they would do if funding was discontinued.

Lack of funding for individuals with complex health needs aged 22 years and older was universally seen as the biggest program challenge. Stakeholders noted that the need for support services on‑reserve for adults (aged 22 and older) remains unmet. Currently, when youth "age-out" of program, the only source of funding to meet their needs is Home Care.

In January of 2016, the Pinaymootang First Nation Health Centre submitted a proposal to INAC to provide young people with complex needs with the support required to transition into adulthood; the proposal was not accepted.

4. My Child, My Heart Program Special Projects

In 2017, My Child, My Heart applied for one-time project funding to develop practice standards and guidelines for implementing Jordan's Principle in First Nation communities across Manitoba. The goals of the project were toFootnote 10:

- Lead the development of Practice Standards and Program Guidelines to support regional implementation of Jordan's Principle across Manitoba;

- Coordinate regional engagement to ensure First Nations lead the development and implementation of Jordan's Principle in every First Nation community; and

- Coordinate stakeholder engagement to ensure input from key stakeholders and service providers into the design of core program components, standards and tools for community-based service delivery as well as regional service coordination.

The Community Advisory Committee developed a Jordan's Principle Regional Working Group to support the achievement of the three coordination goals (previously listed). The budget for this project was $265,852.76. The process utilized to develop the practice standards and guidelines was as followsFootnote 11:

- Project Planning: lead by the Pinaymootang Health Centre Director and Case Manager for the Niniijaanis Nide Program.

- Reviewed the Niniijaanis Nide Program to determine what process and policy could be built on;

- Coordinated and facilitated two planning meetings; and

- Identified themes essential to the guidelines and standards:

- Referral Map Process – including referrals to different aspects of services,

- Utilization of Tele-health capabilities,