Annual Report to Parliament 2020

PDF Version (6.78 MB, 91 pages)

For information regarding reproduction rights, please contact: communicationspublications@canada.ca

Table of contents

Message from the Minister

As Minister of Indigenous Services, I am pleased to share the first ever Indigenous Services Canada annual report to Parliament. The Department of Indigenous Services Act received royal assent on June 21, 2019, legally establishing the new department and its mandate to implement the gradual transfer of departmental responsibilities to Indigenous governments and organizations. This new structure and mandate originates from the important work done by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and its 1996 report that made many insightful recommendations still relevant today. As Prime Minister Trudeau stated in announcing the creation of two new departments: "Over twenty years ago, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples acknowledged that a new relationship with Indigenous peoples would require new structures. It recommended that we dramatically improve the delivery of services while accelerating a move to self-government and self-determination of Indigenous peoples. One mechanism to achieve this was the dissolution of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) and the creation of two new ministries to facilitate this work." As Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada works to advance a nation-to-nation, Inuit-to-Crown, government-to-government, relationship based on rights and respect, Indigenous Services Canada will bolster these efforts by working with Indigenous peoples to support their agency over the design and delivery of services essential to their communities' wellbeing and critical to their self-determination. In the provision of essential services, it is incumbent upon the department to provide funding that is sufficient, stable and predictable in order to close socioeconomic gaps, advance substantive equality, and facilitate a successful transfer of departmental responsibilities to Indigenous organizations. The pandemic that swept the world has had its effect in Canada.

This report provides a general summary of recent COVID-19 measures taken to address service-delivery measures to improve the health and socioeconomic outcomes of Indigenous communities affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, however the collection of further distinctions-based data is underway. Our government's top priority is to continue our efforts to address related impacts, while focusing on economic recovery. Throughout this pandemic, my priority has been to support Indigenous communities to prepare, plan and respond to COVID-19 while thinking about how shorter- and medium-terms measures can contribute to longer-term prosperity. The pandemic has offered an opportunity to think about the needs of Indigenous communities, and has resulted in meaningful conversations that will assist us to build a recovery plan for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities effected by COVID-19.

The necessity and urgency of this important work was highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indigenous communities are incredibly resilient and full of solutions and innovative ideas, as continues to be demonstrated once again throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. This is why measures to improve the health and socioeconomic outcomes of Indigenous communities must be flexible to enable communities to address the specific needs they have identified, in recognition of their right to self-determination.

The Department of Indigenous Services Act stipulates that the annual report to Parliament will describe:

- the socio-economic gaps between First Nations, Inuit, and Métis individuals and other Canadians and the measures taken by the department to reduce those gaps; and

- the progress made towards the transfer of departmental responsibilities to Indigenous organizations.

This report will do so with substantive equality between Indigenous peoples and other Canadians being the overarching goal behind departmental efforts. Substantive equality is a legal principle that refers to the achievement of true equality in outcomes. It is achieved through equal access and opportunity. Most importantly, it is achieved through the provision of services and benefits in a manner and according to standards that meet any unique needs and circumstances, such as cultural, social, economic and historical disadvantage. Success over the long-term will be measured by the extent to which substantive equality is achieved. It has been well-established that Indigenous people in Canada have suffered as a result of systemic racism – as evidenced by, for example, the implementation of the residential school system and the child welfare programs/policies referred to as the 60's Scoop. This historical disadvantage (too often implemented in a context of institutionalized racism) demands acknowledgement and redress if we are to advance a reconciliation agenda with Indigenous partners.

It is for this reason that An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families makes explicit reference to interpreting and administering the Act in accordance with the principles of substantive equality; "in order to secure long-term positive outcomes for Indigenous children, families and communities". This Act received Royal Assent on National Indigenous Peoples Day June 21, 2019; the same day as the legislation legally enabling Indigenous Services Canada. The pursuit of substantive equality and addressing historical disadvantage will inform Indigenous Services Canada policies and programming, as seen in such endeavors as: ensuring provincial comparability in education funding while providing additional language and culture investments; providing increased funding predictably and flexibility through 10-year grants; implementing the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal orders prior to September 2019; efforts to close infrastructure gaps; work to transform Indigenous health services such as the First Nations Health Authority in British Columbia; and, implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

As the newly created department of Indigenous Services Canada continues the work of transferring control over the design, implementation and management of essential services, we know that our efforts must be guided by more respectful ways of working with Indigenous peoples, including listening, being responsive, and forging true partnerships. Indeed, this is the only real path to achieving our important mandate of closing socioeconomic gaps, increasing access to services, and the gradual transfer of those services along with adequate funding, to Indigenous organizations.

To meet our goals of closing socioeconomic gaps and achieving substantive equality, we need information and data to measure progress and identify areas of particular concern. We recognize the importance of this information to Indigenous partners and acknowledge that current distinctions-based Footnote 1 data for Indigenous peoples is woefully insufficient. The data shared in this report is, therefore, a starting point. We are committed to enriching our data sets in each subsequent annual report based on co-developed work that is already underway.Footnote 2 Through emerging tools like the 10-year grants, the First Nations Regional Health Survey, and the Inuit Health Survey, we will be able to share increasingly robust data with Indigenous partners that leads to strengthened policy decisions, targeted approaches, and long-term change. We are also committed to improving data in specific areas like Indigenous education and child and family services to more accurately measure and close these gaps.

We have made important progress in the short time since the creation of Indigenous Services Canada, though we know we are closer to the beginning of our journey than the end. I welcome this opportunity to describe these efforts so far and to further define how we are working to make greater strides going forward in collaboration with Indigenous partners.

I hope this report proves useful in creating a common understanding of these efforts and serves to highlight the importance of Indigenous self-determination to Canada's social cohesion, economy, and people.

The Honourable Marc Miller

Minister of Indigenous Services Canada

Introduction

The Department of Indigenous Services Act and the annual report to Parliament

In August 2017, the Government of Canada announced that Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada would be dissolved and replaced by two new departments; Indigenous Services Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

The Department of Indigenous Services Act came into force on July 15, 2019. The Act opens by confirming that:

the Government of Canada is committed to achieving reconciliation with First Nations, the Métis and the Inuit through renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government and Inuit-Crown relationships based on affirmation and implementation of rights, respect, cooperation and partnership, promoting respect for the rights of Indigenous peoples recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples;

and establishes the new department of Indigenous Services Canada which, in carrying out its activities:

Ensures that Indigenous individuals have access – in accordance with transparent service standards and the needs of each Indigenous group, community or people – to services for which those individuals are eligible,

Takes into account socioeconomic gaps that persist between Indigenous individuals and other Canadians with respect to a range of matters as well as social factors having an impact on health and well-being,

Recognizes and promotes Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing,

Collaborates and cooperates with Indigenous peoples and with the provinces and territories, and

Implements the gradual transfer of departmental responsibilities to Indigenous organizations.

This document is the department's first Annual Report to Parliament, which is required by the Act and described therein as follows:

The Minister must cause to be tabled in each House of Parliament, within three months after the end of the fiscal year or, if the House is not then sitting, on any of the 15 days of the next sitting of the House, a report on (a) the socioeconomic gaps between First Nations individuals, Inuit, Métis individuals and other Canadians and the measures taken by the Department to reduce those gaps; and (b) the progress made towards the transfer of departmental responsibilities to Indigenous organizations.

This first annual report to Parliament is organized into three parts. Part 1 provides a broad overview of the socioeconomic gaps between First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, and the non-Indigenous population in Canada. It covers a wide range of social, economic, and health dimensions, ranging from income and education through life expectancy and language use, and highlights not only what gaps exist today, but how those gaps have evolved over time. This section also highlights why measurement is so important, and the ongoing work being done to address persistent data gaps to make measurement more effective.

Part 2 focuses on the steps that Indigenous Services Canada has taken over the past five years to address specific socioeconomic gaps, as one of a network of federal, provincial/territorial, and local governments providing services to Indigenous people in Canada. This section will discuss the specific activities and initiatives Indigenous Services Canada has undertaken in order to ensure that Indigenous peoples achieve substantive equality: the true equality in outcomes that is achieved through equal access, equal opportunity and the provision of services and benefits in a manner that meets any unique needs and circumstances such as cultural, social, economic, and historical disadvantage (e.g., addressing service gaps, program funding shortages and adjusting policies to achieve better outcomes and meeting population needs).

Part 3 focuses on how the department has been working with Indigenous partners to advance the complex process of transferring control over services to Indigenous peoples. In fulfilling its legislated priority to implement the "gradual transfer of departmental responsibilities to Indigenous organizations," Indigenous Services Canada is working towards a fundamental change in how the rights and needs of Indigenous peoples and communities are addressed by the Government of Canada. This is not a single initiative, but a significant shift in the Government of Canada's role across all public services for Indigenous peoples. By necessity, this shift will not happen overnight or by using a single approach or model. It will take place by working in partnership with Indigenous communities and organizations to find the best paths forward at a pace determined by Indigenous partners. Services for Indigenous peoples continue to be delivered through a complex array of programs, authorities and agreements reflecting the wide range of geographic and socioeconomic realities, as well as the legal and historical contexts of Indigenous communities. It is essential that the new arrangements respect the distinct needs and preferences of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples and uphold treaty rights and federal obligations.

This first report to Parliament presents the department's approach to fulfilling the legislated mandate on transfer of responsibilities and reports on initial advancement of this work. In future years, Indigenous Services Canada will report on the development of partnerships and co-development processes or transfer agreements as well as on empirical metrics of Indigenous control over services that will allow for transparent monitoring of progress.

A note on terminology

We wish to acknowledge at the outset that the use of some terms in this document may be offensive and problematic for some that will read this report. While language in Canada used to describe and speak about Indigenous peoples is evolving to be more respectful and reflective of how Indigenous peoples and communities themselves choose to be identified, there remains some pieces of legislation that continue to use outdated and colonial terminology.

For example, Canada's Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes three distinct "aboriginal peoples of Canada" – "Indian, Inuit, and Métis." The Government of Canada now uses the terms "Indigenous" and "First Nations", however, "Aboriginal" and "Indian" remain the legal terms that continue to be used in certain circumstances.

Also, as the Indian Act, a very outdated and colonial piece of legislation, continues to be in effect terms such as "registered Indian" (also referred to as status Indian) remain in use. Given that these remain accepted legal terms, for the purposes of this report, which requires reference to the Indian Act and its provisions and requires precision in terminology for statistical purposes, the legal terms will be usedFootnote 3.

It is also important to note, that this report uses "Indigenous organizations" to describe the entities to which responsibility for service delivery will be transferred. This term is reflective of the language used in the Department of Indigenous Services Act and is intended to cover a wide range of entities that may take responsibility for the delivery of services including Indigenous governments, authorities, institutions, and organizations, as determined in partnership with Indigenous peoples and communities.

Part 1:

Indigenous populations in Canada

'Indigenous peoples' is a collective name for the original peoples of North America and their descendants. More than 1.67 million people in Canada (4.9% of the population of Canada) self-identified as an Indigenous person on Canada's 2016 Census of Population.Footnote 4 Indigenous peoples are the fastest growing population in Canada, with a population that grew by 42.5% between 2006 and 2016.Footnote 5 Indigenous peoples are also the youngest population in Canada: about 44% were under the age of 25 in 2016, compared to 28% of the non-Indigenous population.

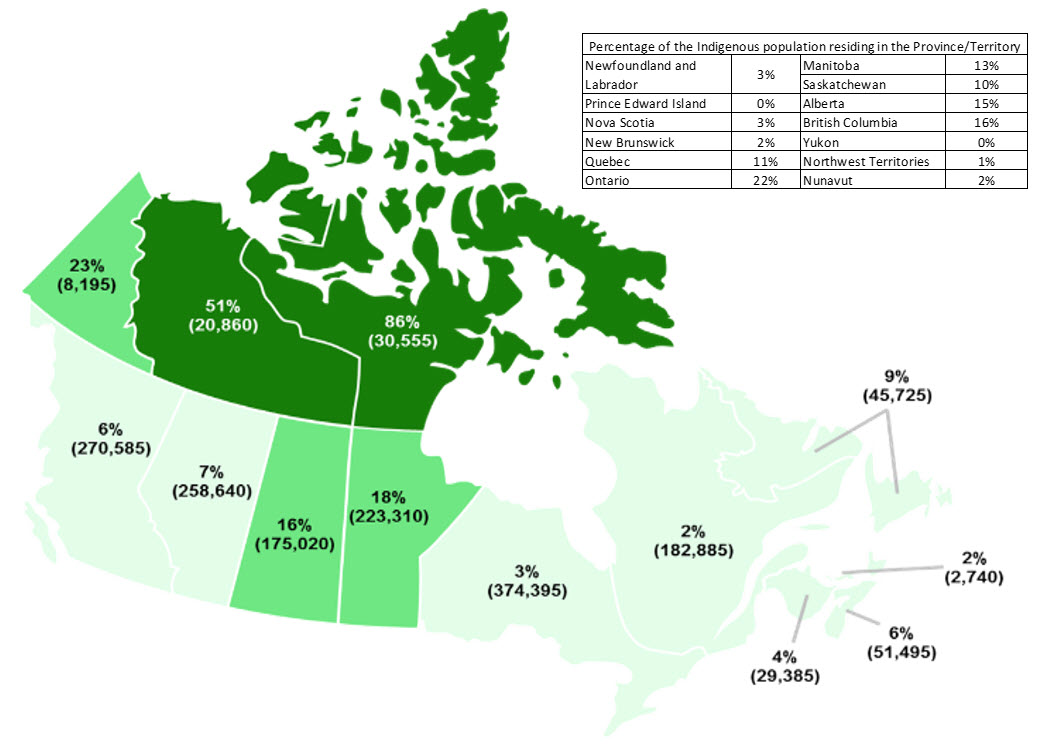

Figure 1 shows the distribution of Indigenous populations across Canada. The figure includes the number of Indigenous individuals living in each province and territory, as well as what proportion of its overall population comprises Indigenous peoples. Indigenous peoples make up the largest proportion of the population in Nunavut (86%), the Northwest Territories (51%) and the Yukon Territory (23%), followed by Manitoba (18%) and Saskatchewan (16%).

The inset table indicates what proportion of the overall Indigenous population resides in each province and territory. Although Indigenous peoples comprise only 3% of Ontario's population, it is home to the largest population of Indigenous peoples: 374, 395 individualsFootnote 6 or 22% of the Indigenous population; 16% of the Indigenous populations resides in British Columbia; followed by 15% in Alberta.

Text alternative for Figure 1: Indigenous Peoples across Canada

| Indigenous | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population size | Percentage | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 45,730 | 9% |

| Prince Edward Island | 2,735 | 2% |

| Nova Scotia | 51,490 | 6% |

| New Brunswick | 29,380 | 4% |

| Quebec | 182,890 | 2% |

| Ontario | 374,395 | 3% |

| Manitoba | 223,310 | 18% |

| Saskatchewan | 175,020 | 16% |

| Alberta | 258,640 | 7% |

| British Columbia | 270,585 | 6% |

| Yukon | 8,195 | 23% |

| Northwest Territories | 20,860 | 51% |

| Nunavut | 30,550 | 86% |

| Percentage of the Indigenous population residing in the Province/Territory | |

|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 3% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0% |

| Nova Scotia | 3% |

| New Brunswick | 2% |

| Quebec | 11% |

| Ontario | 22% |

| Manitoba | 13% |

| Saskatchewan | 10% |

| Alberta | 15% |

| British Columbia | 16% |

| Yukon | 0% |

| Northwest Territories | 1% |

| Nunavut | 2% |

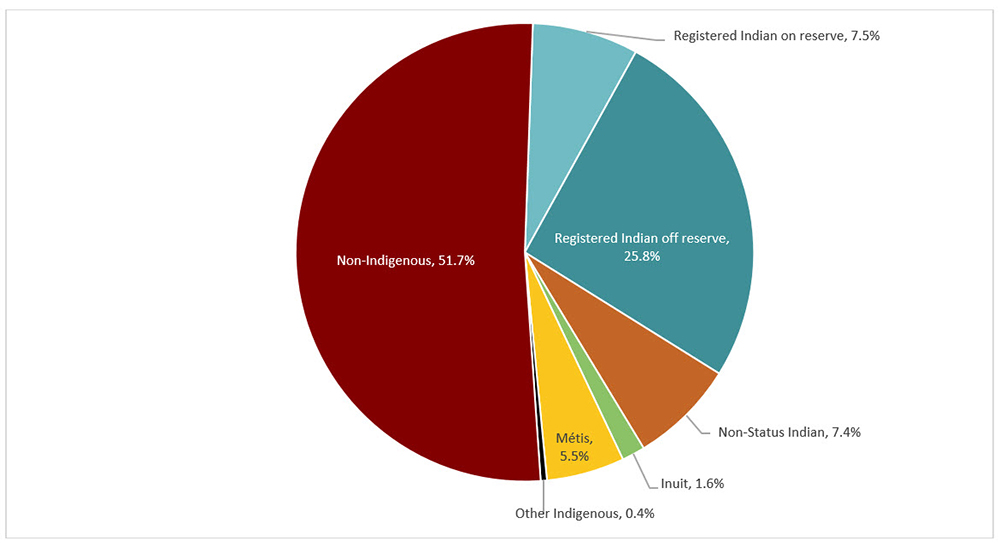

The Canadian Constitution recognizes three groups of Indigenous peoples: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. These are three distinct peoples with unique histories, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs. Figure 2 shows how the composition of Indigenous populations vary across the provinces and territories, and additional information on each of the groups is provided below.

Text alternative for Figure 2: Composition of the Indigenous population in Canada, 2016

| Registered Indian | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Other Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 46% | 23% | 14% | 14% | 2% |

| Prince Edward Island | 44% | 29% | 3% | 23% | 1% |

| Nova Scotia | 37% | 20% | 2% | 40% | 1% |

| New Brunswick | 49% | 17% | 1% | 31% | 2% |

| Quebec | 42% | 16% | 8% | 33% | 1% |

| Ontario | 46% | 23% | 1% | 29% | 1% |

| Manitoba | 57% | 4% | 0% | 38% | 1% |

| Saskatchewan | 63% | 5% | 0% | 32% | 0% |

| Alberta | 48% | 9% | 1% | 41% | 1% |

| British Columbia | 50% | 17% | 1% | 30% | 2% |

| Yukon | 72% | 13% | 3% | 11% | 1% |

| Northwest Territories | 64% | 4% | 19% | 13% | 0% |

| Nunavut | 1% | 0% | 99% | 0% | 0% |

*Other Indigenous refers to respondents who reported more than one identity group, and those who reported being a Band member with no Aboriginal identity and no Registered Indian status.

First Nations

The term 'First Nations people' includes Registered Indians (also called Status Indians) and Non-Status Indians. Registered Indians are individuals registered as Indians under the Indian Act. According to the Census of Canada, there were 820,120 Registered Indians in Canada in 2016, comprising 49% of the Indigenous population. According to the Indian Register, which is an administrative list of all Registered Indians that is maintained by Indigenous Services Canada, there were 970,562 Registered Indians in 2016, and 1,008,955 as of December 30, 2019.Footnote 7

There are 634Footnote 8 First Nation communities in Canada, which represent more than 50 Nations and 50 Indigenous languages.

According to the 2016 Census of Canada, about 40% of Registered Indians live on reserve, 14% live in rural areas (off reserve), and 45% live in urban areas.Footnote 9 70% of First Nations reserve communities have less than 500 inhabitants, while only 4% percent have more than 2,000 inhabitants. They can be relatively urban or extremely remote, and exist throughout Canada. Many First Nations have signed treaties with the Crown.

Non-Status Indians live almost exclusively off reserve. Non-Status Indians account for 14% of the Indigenous population, and about 76% live in urban areas.

Inuit

Inuit are the Indigenous people of the Arctic. The word Inuit means "the people" in the Inuit language of Inuktut. The singular of Inuit is Inuk.

Inuit comprise only 4% of the total Indigenous population, with 64,325 individuals identifying as Inuit on the 2016 Census. The majority (73%) of Inuit live in Inuit Nunangat, which means "the homeland" and represents a third of Canada's land mass and 50% of its coastline. Inuit Nunangat comprises 51 communities across four regionsFootnote 10: Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Northwest Territories and YukonFootnote 11), Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec), and Nunatsiavut (Labrador).

Métis

The term Métis is used to describe communities of mixed European and Indigenous descent across Western Canada, and is defined by the Métis Nation of Canada as a specific community of people, which comprises "distinct Métis communities developed along the routes of the fur trade and across the Northwest within the Métis Nation Homeland. This Homeland includes the three Prairie Provinces (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta), as well as, parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the Northern United States."Footnote 12

According to the 2016 Census, there are 537,855 Métis in Canada, representing about 32% of the Indigenous population. At present, the Census does not distinguish members of the Métis Nation from others who self-identify as Métis.

Measuring the socioeconomic gaps

Why measurement is important

First, continued measurement helps determine whether progress is being achieved over time.

Second, ongoing measurement can help demonstrate whether existing programs and policies are properly designed and resourced, and if there are program and policy gaps that must be addressed.

Third, by tracking program and policy performance and identifying gaps, measurement can help ensure accountability of those who design and implement those programs and policies.

Finally, measurement calls for reflection to define, in a clear and transparent way, what progress means. By stimulating conversation and inviting challenge, the iterative process of defining how to measure progress focuses attention on the things that truly matter.

What is important to measure

The socioeconomic and healthFootnote 13 dimensions addressed in this report, including related indicators, were selected based on a review of the various socioeconomic wellness frameworks being used around the worldFootnote 14, in addition to numerous indicators and frameworks related to well-being and progress that First Nation, Inuit, and Métis governments and organizations have developed and shared with the public online. Where possible, the specific indicators used to measure the different dimensions were based on established national or international methodologies.

Examining gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations is an important way of putting numbers in context. Without a basis for comparison, raw statistics are difficult to interpret. As we will see shortly, for example, the employment rate for Métis is about 70%. It is only by looking at this number in relation to the employment rate for the non-Indigenous population (about 76%), that one can get a sense that the rate for Métis is not as high as it could be, and that there may be a need to address systemic barriers, or enduring effects of past injustices, to support Métis to achieve their employment goals.

It is sometimes suggested that focusing on gaps between different populations is inappropriate as it potentially involves an implicit value judgement. It suggests that the lower-scoring population should aspire to the level of the higher-scoring population on a particular indicator, even if the indicator is of little importance to the lower-scoring population. This is a fair critique, and is why the current report focuses on key socioeconomic indicators that appear regularly in Indigenous wellness frameworks, as well as being recognized internationally as important to quality of life in most cultural contexts. The inclusion of additional indicators, the importance of which might vary across Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, will be done in close consultation with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis for subsequent iterations of this annual report. One exception is knowledge of Indigenous languages, which was included in this inaugural report since it is a well-established priority for many Indigenous peoples.

The indicators

The complete set of indicators addressed in this chapter is listed below, with analyses of each indicator presented in turn in the pages that follow.

| Domain | Indicator | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Income | Median income Median total income for the working age populationFootnote 15, Footnote 16 |

Census of Canada, 2006, 2011Footnote 17, 2016 |

| Poverty Percentage of the population that lived in a low income situation in the year preceding the Census |

Census of Canada, 2006, 2011, 2016 | |

| Employment | Employment rate Percentage of the working age population that was employed on Census reference day |

Census of Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 |

| Median employment income Median employment income received by the working age population in the year prior to the Census |

Census of Canada, 2006, 2011, 2016 | |

| Education | High school completion Percentage of the working age population who had a high school diploma, or who had a post-secondary credential even though they did not complete high school |

Census of Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 |

| University completion Percentage of the working age population with a university degree |

Census of Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 | |

| Family | Foster care Percentage of children and youth aged 0-17 in foster care |

Census of Canada, 2011, 2016 |

| Culture | Indigenous language knowledge Percentage of the population that is able to carry on a conversation in an Indigenous language |

Census of Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 |

| Housing | Crowding Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded (i.e., having more than one person per room) |

Census of Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 |

| State of repair Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair |

Census of Canada, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 | |

| Health | Life expectancy Estimated life expectancy at age 1 |

Statistics Canada, 2006 and 2011 Canadian Census Health and Environment CohortFootnote 18 |

| Infant mortality rate The number of deaths of children under one year of age per 1000 live births |

2004-2006 Canadian Birth-Census Cohort databaseFootnote 19 | |

| Justice | Violent victimization Percentage of the population reporting having been the victim of physical or sexual assault since the age of 15 |

Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces, 2018Footnote 20 |

| Incarceration Custodial admissions as a percentage of the Indigenous and the non-Indigenous population and overrepresentation of Indigenous people in custodial admissions.Footnote 21 |

Adult Correctional Services survey, 2013/2014, 2014/2015, 2015/2016, 2016/2017, 2017/2018 |

Some notes on the approach and methodology

Limitations of the data

Data for the first five sets of indicators (from Income through Housing) are taken from the Census of Canada. This robust source of socioeconomic information remains the cornerstone of data because of its unparalleled ability to support distinctions-based, cross-time analyses for all of Canada, including reserves and the territories.Footnote 22

Despite its richness, the Census has some important limitations. For example, Indigenous people are classified in the Census as Indigenous or not based on self-identification, which can be imperfect given variations in how respondents interpret or understand the Indigenous identity questions, as well as their individual choices respecting whether and how to self-identify as an Indigenous person. In addition, the Census does not capture all First Nation communities. In 2016, there were a total of 14 First Nations communities that were not included, as enumeration was either not permitted, or interrupted before it could be completed. Another important limitation is that the Census of Canada includes a relatively narrow range of socioeconomic indicators, and does not capture the various other dimensions of well-being that are important from an Indigenous perspective.

As we move beyond the Census to seek other sources of data on health, justice, and infrastructure, the persistent gaps in data on Indigenous populations become more evident. In many cases, data are not available on all distinctions groups or geographies, or the data are older and not available across time. Where such limitations exist, the best data available are used to illustrate the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. A section at the end of this chapter is devoted to the gaps in Indigenous data, steps that have been taken to address them, and what further efforts can be made to ensure that all partners and stakeholders have the data required to support services to Indigenous peoples, and the transfer of services responsibilities to Indigenous control.

The analysis

To the extent possible, this analysis is distinctions-based and includes data for the past 15 years, to illustrate how socioeconomic gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations have evolved.

Data are presented for the three main distinctions groups: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. First Nations data are further disaggregated, given the significant differences in socioeconomic outcomes that are known to exist among the following groups: Registered Indians living on reserve, Registered Indians living off reserve, and Non-Status Indians.

Regional and genderFootnote 23-based analyses are also provided. Notably, some very small populations of First Nations and Métis in the territories are also the populations experiencing the largest gaps relative to the non-Indigenous population. Because statistics based on very small populations are less reliable, and can create a skewed image of overall trends, one option would be to exclude them from broader analyses and/or discuss them separately. In the interest of transparency, however, it was decided to retain these small populations as part of the general analysis. Readers are encouraged to interpret statistics for small populations with caution, especially when data are further broken down by gender, age or other variables.Footnote 24

Findings

Income – median income

Median income is a well-established measure of material well-being. Although it does not capture an individual's assets, median income is one way of estimating a person's wealth.

Figure 3 below compares median income for the working age population (aged 25-64) across population groups. The gap in median income is largest for Registered Indians living on reserve, whose median income is less than half that of the non-Indigenous population. Registered Indians living off reserve, Non-Status Indians, and Inuit each have a median income that is between about 75% and 80% of the non-Indigenous population median income. Métis have a median income that is nearly on par with that of non-Indigenous Canadians.

Text alternative for Figure 3: Median income, 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median income | $20,357 | $32,553 | $34,458 | $33,135 | $40,814 | $42,930 |

Figure 4 below shows how median incomeFootnote 25 has evolved over time. The most striking reduction in the income gap occurred among the Métis, though the gap also narrowed for Registered Indians living off reserve and Non-Status Indians. The median income gaps observed for Registered Indians living on reserve and Inuit, however, changed little.

Text alternative for Figure 4: Median income, 2005 – 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | $16,441 | $25,671 | $28,501 | $28,729 | $32,601 | $38,731 |

| 2010 | $16,905 | $30,021 | $32,286 | $31,767 | $37,482 | $41,225 |

| 2015 | $20,357 | $32,553 | $34,458 | $33,135 | $40,814 | $42,930 |

Region matters

The national picture of the median income gap between First Nations and the non-Indigenous population can conceal important regional differences. As Figure 5 illustrates, for example, Registered Indians living on reserve in Newfoundland and Labrador have a median income that is about 80% that of the non-Indigenous population, while Registered Indians living on reserve in Saskatchewan have a median income that is only 31% as large as that of Saskatchewan's non-Indigenous population – a difference of more than $34,000 annually.

Text alternative for Figure 5: Median income, 2015, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $33,088 | $36,853 | $37,310 | $41,263 |

| Prince Edward Island | $26,048 | $31,538 | $29,142 | $38,427 |

| Nova Scotia | $18,778 | $35,577 | $32,827 | $39,185 |

| New Brunswick | $22,209 | $31,807 | $29,024 | $38,064 |

| Quebec | $31,964 | $34,312 | $34,590 | $40,856 |

| Ontario | $22,708 | $32,708 | $32,643 | $42,564 |

| Manitoba | $15,973 | $28,061 | $33,972 | $43,286 |

| Saskatchewan | $15,367 | $30,980 | $34,016 | $49,418 |

| Alberta | $19,512 | $38,262 | $45,865 | $53,306 |

| British Columbia | $19,613 | $29,680 | $33,477 | $41,430 |

| Yukon | N/A | $39,625 | $52,538 | $58,757 |

| Northwest Territories | $27,072 | $38,555 | $61,362 | $82,965 |

| Nunavut | N/A | $83,456 | $92,416 | $106,569 |

Regional differences are less pronounced among Métis, whose median income ranges from 79% (in Nunavut) to 107% (in Newfoundland and Labrador) that of the non-Indigenous populations in those regions (Figure 6). It is worth noting that in Nunavut, where the most dramatic gap appears, only 140 people identified as Métis on the 2016 Census.

Text alternative for Figure 6: Median income, 2015, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $44,224 | $41,263 |

| Prince Edward Island | $35,866 | $38,427 |

| Nova Scotia | $37,640 | $39,185 |

| New Brunswick | $33,282 | $38,064 |

| Quebec | $36,373 | $40,856 |

| Ontario | $40,197 | $42,564 |

| Manitoba | $41,385 | $43,286 |

| Saskatchewan | $43,696 | $49,418 |

| Alberta | $47,419 | $53,306 |

| British Columbia | $37,487 | $41,430 |

| Yukon | $52,423 | $58,757 |

| Northwest Territories | $76,515 | $82,965 |

| Nunavut | $83,712 | $106,569 |

Figure 7 below illustrates the regional variations in the median income gap between Inuit and the non-Indigenous population. The gaps in each of the four regions of Inuit Nunangat are quite wide, with Inuit receiving between 28.3% (in Nunavut) and 49.8% (in Nunatsiavut) of what the non-Indigenous population receives. It is worth noting that these large gaps reflect the high median incomes of the non-Indigenous population living in Inuit Nunangat. Outside of Inuit Nunangat, the non-Indigenous population's median income is much lower, and the gap is comparatively narrow.

Text alternative for Figure 7: Median income, 2015, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (NWT and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | $31,792 | $35,524 | $31,424 | $30,190 | $36,116 |

| Non-Indigenous | $63,872 | $81,408 | $94,362 | $106,569 | $42,921 |

Gender mattersFootnote 26

For the non-Indigenous population in Canada, the median income for men is higher than the median income for women by approximately $13,500. As Figure 8 below illustrates, this pattern is different for Indigenous populations, particularly among Inuit, where men and women have a similar median income, and among Registered Indians living on reserve, where women's median income is more than $6,000 higher than that of men's. As a consequence, when one focused on data for men specifically, the gap in median income is particularly large: Registered Indian men living on reserve have a median income that is only about one third as large as the median income for non-Indigenous men; and Inuit men have a median income that is about two-thirds as large.

Text alternative for Figure 8: Median income, 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by gender, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | $17,042 | $37,882 | $40,707 | $32,560 | $50,004 | $50,523 |

| Female | $23,296 | $29,602 | $30,180 | $33,434 | $34,509 | $36,997 |

Income – Low income measure

The low income measure is one way of assessing the level of poverty in a population. A person is considered to be living in a low income situation if they are part of a household whose total income (after tax) is less than half of the national median household income, adjusted for household size. The low income threshold in 2015 was $22,133 for a single person, and $44,266 for a family of four.Footnote 27

Figure 9 below compares the percentage of the population who were living in a low income situation in 2015.

Text alternative for Figure 9: Percentage living in a low income situation, 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage living in a low income situation | 47.7% | 30.3% | 25.2% | 22.3% | 17.3% | 13.8% |

Members of all Indigenous groups are more likely than the non-Indigenous population to be living in a situation of low income. Registered Indians living on reserve are 3.5 times more likely.

Figure 10 below illustrates that the likelihood of living in a low income situation decreased between 2005 and 2015 for each Indigenous group, particularly Registered Indians living off reserve. Since the likelihood for the non-Indigenous population stayed stable at around 14%, the gaps also narrowed for each Indigenous group – by as much as 6.6 percentage points for Registered Indians living off reserve.

Text alternative for Figure 10: Percentage living in a low income situation, 2005-2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 50.7% | 36.7% | 27.5% | 26.3% | 21.0% | 13.6% |

| 2010 | 54.1% | 31.9% | 25.3% | 22.9% | 19.5% | 14.5% |

| 2015 | 47.7% | 30.3% | 25.2% | 22.3% | 17.3% | 13.8% |

Region matters

Once again, wide variation is evident across the provinces and territories with respect to the percentage of populations living in low income situations. Manitoba and Saskatchewan stand out as having the largest gaps between non-Indigenous and First Nations populations (Figure 11).

Text alternative for Figure 11: Percentage living in a low income situation, 2015, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 14.1% | 17.5% | 18.3% | 15.3% |

| Prince Edward Island | 34.6% | 31.1% | 35.0% | 16.7% |

| Nova Scotia | 55.3% | 20.7% | 24.5% | 17.1% |

| New Brunswick | 47.8% | 26.4% | 33.7% | 16.8% |

| Quebec | 26.3% | 25.7% | 21.3% | 14.5% |

| Ontario | 43.1% | 27.4% | 26.2% | 14.2% |

| Manitoba | 59.6% | 44.1% | 38.9% | 13.1% |

| Saskatchewan | 59.5% | 39.6% | 37.5% | 10.7% |

| Alberta | 48.4% | 24.1% | 19.6% | 8.8% |

| British Columbia | 42.3% | 31.1% | 24.9% | 15.1% |

| Yukon | N/A | 24.5% | 19.1% | 7.4% |

| Northwest Territories | 19.3% | 20.2% | 19.4% | 4.3% |

| Nunavut | N/A | 11.8% | 12.5% | 2.4% |

With the exception of Newfoundland and Labrador, Métis in all regions are more likely than the non-Indigenous population to be in a low income situation: ranging from a difference of only about one percentage point in Nova Scotia, to seven percentage points in Saskatchewan (Figure 12).

Text alternative for Figure 12: Percentage living in a low income situation, 2015, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 12.6% | 15.3% |

| Prince Edward Island | 20.6% | 16.7% |

| Nova Scotia | 18.2% | 17.1% |

| New Brunswick | 23.7% | 16.8% |

| Quebec | 19.8% | 14.5% |

| Ontario | 17.8% | 14.2% |

| Manitoba | 18.3% | 13.1% |

| Saskatchewan | 17.7% | 10.7% |

| Alberta | 13.3% | 8.8% |

| British Columbia | 18.3% | 15.1% |

| Yukon | 11.3% | 7.4% |

| Northwest Territories | 8.6% | 4.3% |

| Nunavut | 7.1% | 2.4% |

As Figure 13 illustrates, the low income gap between Inuit and the non-Indigenous population outside Inuit Nunangat is similar to the national gap that was shown in Figure 9. The gaps are much higher in the four Inuit regions, however, where the percentage of Inuit in a low income situation exceeds that of the non-Indigenous population by between 12.6 (in Nunavik) 23.6 (in Nunavut) percentage points.

Text alternative for Figure 13: Percentage living in a low income situation, 2015, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (NWT and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | 22.5% | 14.4% | 24.0% | 26.0% | 20.8% |

| Non-Indigenous | 4.8% | 1.8% | 7.0% | 2.4% | 13.8% |

A focus on gender

Figure 14 illustrates that, although there is a greater tendency to be living in a low income situation among women than among men, differences are relatively small. Consequently, the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous males do not differ in a marked or consistent way from the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous females.

Text alternative for Figure 14: Percentage living in a low income situation, 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, by gender, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 47.7% | 28.4% | 24.3% | 22.1% | 16.0% | 13.1% |

| Female | 47.7% | 31.9% | 26.1% | 22.5% | 18.5% | 14.5% |

Employment – employment rate

Employment rate is one way of measuring a population's economic health, and is simply the percentage of the working age population (aged 25-64) who have a job.

Figure 15 demonstrates that all Indigenous populations – particularly Registered Indians living on reserve – have lower employment rates than the non-Indigenous population.

Text alternative for Figure 15: Employment rate, 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment rate | 46.9% | 60.2% | 66.1% | 57.4% | 70.4% | 76.0% |

Figure 16 below demonstrates that employment rates have been relatively stable over time. The gaps relative to the non-Indigenous population narrowed slightly for Registered Indians living off reserve, Non-Status Indians, and Métis, but increased slightly for Registered Indians living on reserve and Inuit.

Text alternative for Figure 16: Employment rate, 2001 – 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 48.1% | 56.4% | 63.3% | 59.0% | 67.9% | 75.1% |

| 2006 | 50.2% | 61.8% | 67.4% | 59.7% | 71.5% | 76.3% |

| 2011 | 46.8% | 61.2% | 67.0% | 58.6% | 71.6% | 75.8% |

| 2016 | 46.9% | 60.2% | 66.1% | 57.4% | 70.4% | 76.0% |

Region matters

Employment rates for First Nations vary widely across the provinces and territories. Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Northwest Territories stand out as having the largest gaps between non-Indigenous and First Nations populations (Figure 17). In Saskatchewan, for example, the gaps are 42.7, 27.0, and 21.6 percentage points wide for Registered Indians on reserve, Registered Indians off reserve, and Non-Status Indians, respectively.

Text alternative for Figure 17: Employment rate, 2016, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 50.2% | 60.8% | 61.1% | 64.9% |

| Prince Edward Island | 50.0% | 61.3% | 61.3% | 74.5% |

| Nova Scotia | 47.8% | 67.2% | 64.9% | 72.0% |

| New Brunswick | 46.3% | 62.2% | 58.5% | 71.3% |

| Quebec | 55.2% | 63.3% | 68.6% | 75.7% |

| Ontario | 52.7% | 62.3% | 64.5% | 76.0% |

| Manitoba | 40.0% | 52.4% | 64.8% | 79.6% |

| Saskatchewan | 38.0% | 53.7% | 59.1% | 80.7% |

| Alberta | 43.6% | 62.4% | 69.5% | 77.7% |

| British Columbia | 51.9% | 61.5% | 69.3% | 75.8% |

| Yukon | N/A | 58.7% | 77.5% | 83.5% |

| Northwest Territories | 51.9% | 59.3% | 66.7% | 87.7% |

| Nunavut | N/A | 85.7% | 81.8% | 92.2% |

As shown in Figure 18, the employment rate gap for Métis is up to ten percentage points wide in some regions (New Brunswick, Quebec, and Saskatchewan), and in other regions, however, the gap is very small. In Prince Edward Island, the employment rate for Métis is actually slightly higher than that of the non-Indigenous population.

Text alternative for Figure 18: Employment rate, 2016, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 56.9% | 64.9% |

| Prince Edward Island | 75.8% | 74.5% |

| Nova Scotia | 71.3% | 72.0% |

| New Brunswick | 61.3% | 71.3% |

| Quebec | 65.9% | 75.7% |

| Ontario | 69.8% | 76.0% |

| Manitoba | 73.7% | 79.6% |

| Saskatchewan | 71.6% | 80.7% |

| Alberta | 71.0% | 77.7% |

| British Columbia | 71.7% | 75.8% |

| Yukon | 80.2% | 83.5% |

| Northwest Territories | 80.3% | 87.7% |

| Nunavut | 85.7% | 92.2% |

Figure 19 illustrates that the employment rate gaps for Inuit are smallest – at 15.5 percentage points wide – outside Inuit Nunangat. Inside Inuit Nunangat, the smallest gap is in Inuvialuit Settlement Region (29.1 percentage points), and the largest in Nunavut (38.5 percentage points).

Text alternative for Figure 19: Employment rate, 2016, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (NWT and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | 48.2% | 63.7% | 58.8% | 53.7% | 60.5% |

| Non-Indigenous | 77.4% | 94.6% | 87.9% | 92.2% | 76.0% |

A focus on gender

The employment rate gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations is larger among males than among females. For example, while the gap between female Registered Indians living on reserve and non-Indigenous females was 23.9 percentage points wide, the gap when similarly compared among males, was 34.5 percentage points wide (Figure 20).

Text alternative for Figure 20: Employment rate, 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by gender, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 45.5% | 63.8% | 68.9% | 56.9% | 72.6% | 80.0% |

| Female | 48.2% | 57.3% | 63.7% | 57.8% | 68.4% | 72.1% |

Employment – employment income

Median employment income complements employment rate, as it is a common way of assessing the quality of jobs held by the employed population.

Figure 21 illustrates substantial gaps in median employment income between the non-Indigenous population and First Nations and Inuit.

Text alternative for Figure 21: Median employment income, 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median employment income | $23,298 | $35,390 | $36,457 | $32,673 | $41,440 | $42,660 |

Figure 22 below shows how median employment income (adjusted to account for inflation) has evolved over time. Although median employment income has increased for each group, the gap relative to the non-Indigenous population has decreased for Registered Indians living off reserve, Non-Status Indians, and Métis only. The median employment income gaps for Inuit and Registered Indians living on reserve have changed little.

Text alternative for Figure 22: Median employment income, 2005 – 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | $20,954 | $29,650 | $32,156 | $30,336 | $34,762 | $40,137 |

| 2010 | $24,509 | $35,282 | $35,959 | $32,866 | $39,910 | $42,974 |

| 2015 | $23,298 | $35,390 | $36,457 | $32,673 | $41,440 | $42,660 |

Region matters

The national median employment income gaps can conceal important regional differences. As Figure 23 illustrates, for example, Registered Indians living on reserve in Quebec have a median employment income that is about 74% that of the non-Indigenous population, whereas Registered Indians living on reserve in Saskatchewan and New Brunswick have a median income that are only 44% as large as that of the non-Indigenous population in those provinces – differences of $26,172 and $20,485, respectively. The largest gap for First Nations is for the small group of approximately 130 Registered Indians living on reserve in the Northwest Territories, at more than $59,000.

Text alternative for Figure 23: Median employment income, 2015, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $20,928 | $36,409 | $37,668 | $40,816 |

| Prince Edward Island | $16,960 | $26,755 | $27,301 | $34,927 |

| Nova Scotia | $23,509 | $35,178 | $33,450 | $37,979 |

| New Brunswick | $16,374 | $28,722 | $29,651 | $36,859 |

| Quebec | $28,605 | $33,960 | $33,718 | $38,744 |

| Ontario | $25,567 | $37,774 | $36,388 | $43,879 |

| Manitoba | $20,137 | $30,940 | $34,229 | $42,332 |

| Saskatchewan | $20,964 | $32,517 | $38,670 | $47,136 |

| Alberta | $23,910 | $42,185 | $48,350 | $52,838 |

| British Columbia | $22,624 | $32,363 | $35,395 | $41,574 |

| Yukon | N/A | $40,295 | $52,582 | $56,389 |

| Northwest Territories | $22,080 | $40,463 | $71,680 | $81,106 |

| Nunavut | N/A | $77,312 | $82,176 | $104,294 |

As Figure 24 illustrates, the small employment income gap that is seen for Métis at the national level is similarly small in most regions. New Brunswick and NunavutFootnote 28 are exceptions, where median employment incomes for Métis are 80% and 81% that of the non-Indigenous population in those regions, respectively. By contrast, the median income of the approximately 6,625 Métis in Newfoundland and Labrador is more than $3,000 higher than that of the non-Indigenous population in the province.

Text alternative for Figure 24: Median employment income, 2015, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | $44,107 | $40,816 |

| Prince Edward Island | $31,998 | $34,927 |

| Nova Scotia | $34,810 | $37,979 |

| New Brunswick | $29,406 | $36,859 |

| Quebec | $34,746 | $38,744 |

| Ontario | $42,299 | $43,879 |

| Manitoba | $41,929 | $42,332 |

| Saskatchewan | $44,594 | $47,136 |

| Alberta | $48,658 | $52,838 |

| British Columbia | $38,104 | $41,574 |

| Yukon | $55,724 | $56,389 |

| Northwest Territories | $77,381 | $81,106 |

| Nunavut | $84,736 | $104,294 |

Figure 25 shows that, outside Inuit Nunangat, the employment income gap for Inuit is relatively narrow, with Inuit earning 91% of the employment income earned by the non-Indigenous population. Within Inuit Nunangat, however, the median employment income for Inuit is between about one half (in Nunatsiavut) and one third (in Nunavut) that of the non-Indigenous population.

Text alternative for Figure 25: Median employment income, 2015, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (NWT and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | $30,272 | $28,565 | $30,304 | $30,039 | $38,707 |

| Non-Indigenous | $58,368 | $79,680 | $94,400 | $104,294 | $42,650 |

A focus on gender

Figure 26 illustrates that, Métis excepted, the gap in median employment income between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations is larger among males than among females. For example, female Registered Indians living on reserve earned 67% of the employment income earned by non-Indigenous women (a difference of $11,881). By contrast, Registered Indian males living on reserve earned 44% of the employment income earned by non-Indigenous males (a difference of $28,529).

Text alternative for Figure 26: Median employment income, 2015, Indigenous and non-Indigenous Populations, aged 25-64, by gender, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | $22,218 | $42,838 | $44,498 | $34,344 | $51,282 | $50,747 |

| Female | $24,205 | $30,034 | $30,165 | $31,097 | $34,002 | $36,086 |

Education – having at least a high school credential

In addition to being a baseline requirement for many careers, completing a formal education at the high school level or above has the added benefit of ensuring that individuals have the literacy, numeracy, and other skills they need to participate fully in Canada's economy and in civil society, and to effectively access the services and benefits to which they are entitled.

Figure 27 demonstrates that significant gaps in high school completionFootnote 29 exist between Indigenous populations – particularly First Nations living on reserve and Inuit – and the non-Indigenous population in Canada.

Text alternative for Figure 27: Percentage with at least a high school credential, 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage with at least a high school credential | 57.0% | 75.0% | 80.3% | 55.9% | 82.3% | 89.2% |

Figure 28 illustrates that levels of high school completion have increased slowly over time for all Indigenous groups, as well as for the non-Indigenous population. The gaps narrowed somewhat for Non-Status Indians and Métis, were unchanged for Registered Indians living off reserve, and widened about six and seven percentage points for Registered Indians living on reserve and Inuit, respectively.

Text alternative for Figure 28: Percentage with at least a high school credential, 2001 – 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 51.3% | 63.6% | 65.9% | 51.8% | 66.7% | 77.7% |

| 2006 | 50.0% | 68.0% | 71.5% | 48.6% | 74.4% | 85.2% |

| 2011 | 53.5% | 72.9% | 77.7% | 51.5% | 79.6% | 87.9% |

| 2016 | 57.0% | 75.0% | 80.3% | 55.9% | 82.3% | 89.2% |

Region matters

High school completion varies widely across the provinces and territories. The Prairie provinces and the Northwest Territories stand out as having the largest gaps between non-Indigenous and First Nations populations (Figure 29).

Text alternative for Figure 29: Percentage with at least a high school credential, 2016, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 52.8% | 83.4% | 85.2% | 84.6% |

| Prince Edward Island | 65.4% | 90.7% | 77.0% | 88.1% |

| Nova Scotia | 73.8% | 85.1% | 87.2% | 88.0% |

| New Brunswick | 74.3% | 82.0% | 80.5% | 86.4% |

| Quebec | 56.9% | 76.9% | 79.0% | 87.0% |

| Ontario | 60.6% | 79.2% | 80.5% | 89.9% |

| Manitoba | 46.1% | 67.7% | 75.0% | 88.8% |

| Saskatchewan | 54.1% | 73.1% | 73.8% | 90.5% |

| Alberta | 52.4% | 72.7% | 77.6% | 90.1% |

| British Columbia | 65.4% | 74.6% | 80.5% | 91.1% |

| Yukon | N/A | 72.6% | 91.0% | 92.6% |

| Northwest Territories | 50.0% | 57.5% | 71.7% | 93.7% |

| Nunavut | N/A | 90.5% | 81.8% | 96.1% |

Regional variation in high school attainment is modest among Métis, and the gaps relative to the non-Indigenous population range from a low of one percentage point in Prince Edward Island to a high of almost 14 percentage points in the Northwest Territories (Figure 30).

Text alternative for Figure 30: Percentage with at least a high school credential, 2016, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 82.5% | 84.6% |

| Prince Edward Island | 87.1% | 88.1% |

| Nova Scotia | 84.7% | 88.0% |

| New Brunswick | 78.0% | 86.4% |

| Quebec | 81.0% | 87.0% |

| Ontario | 86.1% | 89.9% |

| Manitoba | 80.2% | 88.8% |

| Saskatchewan | 81.3% | 90.5% |

| Alberta | 79.8% | 90.1% |

| British Columbia | 84.2% | 91.1% |

| Yukon | 87.3% | 92.6% |

| Northwest Territories | 80.0% | 93.7% |

| Nunavut | 85.0% | 96.1% |

Figure 31 illustrates that, outside Inuit Nunangat, the high school completion gap for Inuit is comparatively small: the rate of high school completion for the non-Indigenous population exceeds that of Inuit by 12 percentage points. Within Inuit Nunangat, however, the gaps range from 30 (in Nunatsiavut) to 56 (in Nunavik) percentage points wide.

Text alternative for Figure 31: Percentage with at least a high school credential, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (NWT and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | 63.2% | 41.0% | 53.4% | 47.0% | 76.7% |

| Non-Indigenous | 93.3% | 96.7% | 94.5% | 95.8% | 89.2% |

Changes in a population's education levels tend to start with youth. As the availability of and need for formal education expands, young people strive to obtain the credentials they need to achieve their career goals. Although older adults can and do obtain additional educational credentials, most people complete their formal education when they are relatively younger. According to the 2016 Census, for example, while 64% of Indigenous people aged 15-24 who did not already have a high school diploma were enrolled in school, only 2% of those over 45 were enrolled. Looking at the educational attainment of younger cohorts, therefore, can provide some insight into how the overall education gap can be expected to change in the future. Simply put, if the gaps are smaller among younger cohorts, the overall gaps are in the process of narrowing.

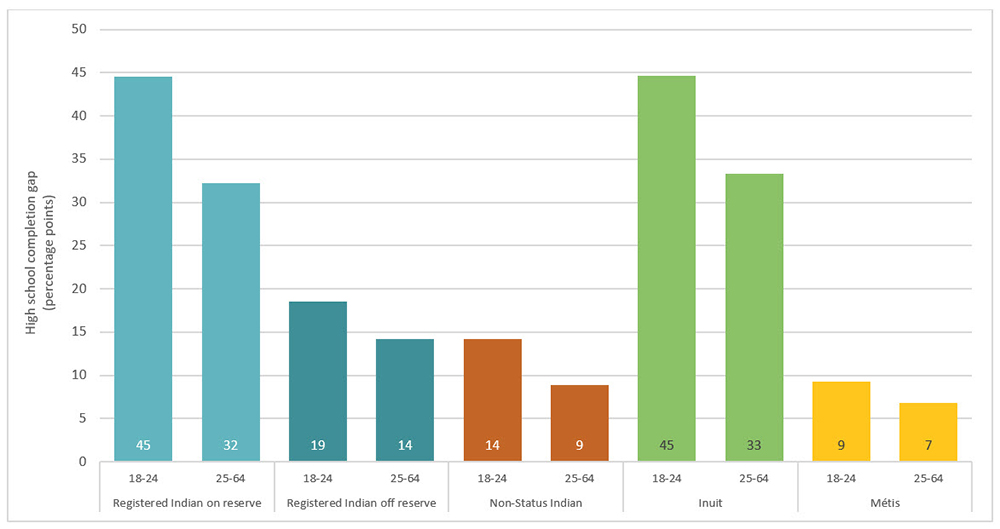

As Figure 32 demonstrates, the gaps among the younger cohort are actually slightly larger than the gaps among the older cohort, suggesting that the high school completion gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations are not on track to narrow in the short term.

Text alternative for Figure 32: High school completion gap (in percentage points) between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 18-24 and 25-64, 2016, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 18-24 | 45 | 19 | 14 | 45 | 9 |

| Aged 25-64 | 32 | 14 | 9 | 33 | 7 |

A focus on gender

Unlike other socioeconomic indicators like income and employment, women tend to have higher levels of educational attainment than men. Figure 33 demonstrates that high school completion gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations tend to be larger among males than among females. For example, among Registered Indians living on reserve, the high school completion gap relative to the non-Indigenous population is 34.9 percentage points wide for males, but 29.5 percentage points wide for females.

Text alternative for Figure 33: Percentage with at least a high school credential, 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by gender, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 52.9% | 72.4% | 76.9% | 54.8% | 79.1% | 87.7% |

| Female | 61.0% | 77.2% | 83.3% | 56.8% | 85.3% | 90.6% |

Education – completion of a university degree

Although not everyone wants or needs a university degree to fulfil their career goals, those with a university degree still have the highest incomes in Canada, and a degree can generally expand one's employment options as well as providing advanced skills that can be assets in various domains of life.

Figure 34 below illustrates the significant gaps in university attainment that exist for all Indigenous groups, most notably First Nations living on reserve and Inuit, who are less than one-fifth as likely as the non-Indigenous population to have a university degree.

Text alternative for Figure 34: Percentage with a university degree, 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage with a university degree | 5.4% | 11.3% | 11.9% | 5.3% | 13.6% | 29.3% |

Figure 35 demonstrates that the university gap in the working age population (aged 25-64) has been widening for all Indigenous groups relative to the non-Indigenous population. Although First Nations, Inuit, and Métis all saw increases in university attainment between 2001 and 2016, none increased quickly enough to keep pace with the non-Indigenous population. Moreover, as Figure 36 illustrates, the gaps are wider among younger people (aged 25-34), suggesting that disparities in university completion are not poised to improve in the short term.

Text alternative for Figure 35: Percentage with a university degree, 2001 – 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 3.4% | 6.8% | 7.0% | 2.5% | 7.2% | 20.1% |

| 2006 | 4.4% | 9.0% | 7.9% | 3.7% | 9.2% | 23.4% |

| 2011 | 4.7% | 11.0% | 10.7% | 5.1% | 12.1% | 26.5% |

| 2016 | 5.4% | 11.3% | 11.9% | 5.3% | 13.6% | 29.3% |

Text alternative for Figure 36: University completion gap (in percentage points) between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-34 and 25-64, 2016, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 25-34 | 34 | 25 | 22 | 32 | 19 |

| Aged 25-64 | 24 | 18 | 17 | 24 | 16 |

Region matters

Figure 37 illustrates the marked variations in university completion gaps for First Nations across regions. The gaps tend to be less pronounced in the Atlantic provinces, where university completion among the non-Indigenous population is lower. Figure 38 shows a similar pattern among Métis.

Text alternative for Figure 37: Percentage with a university degree, 2016, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 3.8% | 14.1% | 16.8% | 18.8% |

| Prince Edward Island | 5.8% | 22.7% | 9.8% | 23.9% |

| Nova Scotia | 15.1% | 19.2% | 14.9% | 25.9% |

| New Brunswick | 8.2% | 15.1% | 10.4% | 20.5% |

| Quebec | 5.7% | 13.0% | 11.4% | 25.9% |

| Ontario | 5.2% | 12.7% | 11.7% | 32.4% |

| Manitoba | 5.2% | 9.6% | 9.7% | 28.0% |

| Saskatchewan | 5.1% | 11.8% | 10.5% | 24.5% |

| Alberta | 4.1% | 9.5% | 11.2% | 29.2% |

| British Columbia | 5.0% | 10.0% | 11.3% | 31.0% |

| Yukon | N/A | 9.3% | 15.7% | 35.3% |

| Northwest Territories | 0.0% | 5.2% | 8.3% | 38.2% |

| Nunavut | N/A | 23.8% | 36.4% | 50.6% |

Text alternative for Figure 38: Percentage with a university degree, 2016, Métis and Non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 12.1% | 18.8% |

| Prince Edward Island | 19.4% | 23.9% |

| Nova Scotia | 17.9% | 25.9% |

| New Brunswick | 10.3% | 20.5% |

| Quebec | 13.7% | 25.9% |

| Ontario | 16.0% | 32.4% |

| Manitoba | 12.8% | 28.0% |

| Saskatchewan | 12.9% | 24.5% |

| Alberta | 12.0% | 29.2% |

| British Columbia | 13.0% | 31.0% |

| Yukon | 16.7% | 35.3% |

| Northwest Territories | 17.1% | 38.2% |

| Nunavut | 35.0% | 50.6% |

Figure 39 demonstrates the very large gaps in university completion that exist between Inuit and the non-Indigenous population, even outside of Inuit Nunangat. Within Inuit Nunangat, almost half of the non-Indigenous population in each region has a university degree, compared to only a very small percentage of Inuit.

Text alternative for Figure 39: Percentage with a university degree, 2016, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (NWT and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | 4.0% | 1.1% | 3.0% | 2.6% | 12.0% |

| Non-Indigenous | 46.7% | 48.9% | 47.9% | 50.5% | 29.3% |

A focus on gender

As Figure 40 demonstrates, the university completion gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations are similar for males and females.

Text alternative for Figure 40: Percentage with a university degree, 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, aged 25-64, by gender, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 2.9% | 8.0% | 9.0% | 3.4% | 10.7% | 26.9% |

| Female | 7.8% | 14.1% | 14.4% | 7.0% | 16.3% | 31.7% |

Housing – crowding

The World Health Organization identified overcrowding as a major factor in the transmission of diseasesFootnote 30,Footnote 31, and it has been linked to other adverse outcomes such as behavioural issues among children.Footnote 32 While the likelihood that one will live in a crowded dwelling is largely a function of one's income or wealth, it is also impacted by the availability of housing and other aspects of local housing markets, and therefore should be measured separately.

Figure 41 below illustrates that crowdedFootnote 33 dwellings are rare in the non-Indigenous population, even though, as seen above, 13.8% of that population is living in a low income situation. Crowded dwellings are similarly rare among Registered Indians living off reserve, Non-Status Indians, and Métis. By contrast, the crowding gaps measured for Registered Indians living on reserve and Inuit are substantial, and, as Figure 42 illustrates, have changed little since 2001.

Text alternative for Figure 41: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded | 12.7% | 2.7% | 1.1% | 16.0% | 0.8% | 1.8% |

Text alternative for Figure 42: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2001 – 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 13.8% | 3.8% | 1.3% | 15.3% | 1.5% | 1.3% |

| 2006 | 12.6% | 3.4% | 1.3% | 16.3% | 1.2% | 1.4% |

| 2011 | 13.1% | 3.4% | 1.4% | 15.6% | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| 2016 | 12.7% | 2.7% | 1.1% | 16.0% | 0.8% | 1.8% |

Region matters

As Figure 43 illustrates, crowding among First Nations is overwhelmingly an issue for those living on reserve, particularly in the Prairie provinces, although Registered Indians living off reserve experience crowding gaps relative to the non-Indigenous populations in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and the Northwest Territories.

Text alternative for Figure 43: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2016, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 14.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 0.5% |

| Nova Scotia | 4.5% | 0.2% | 0.9% | 0.5% |

| New Brunswick | 2.3% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 0.5% |

| Quebec | 10.6% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 1.1% |

| Ontario | 8.3% | 1.4% | 1.0% | 2.4% |

| Manitoba | 23.1% | 5.1% | 1.8% | 2.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 18.9% | 5.7% | 3.0% | 1.5% |

| Alberta | 17.6% | 3.3% | 1.2% | 2.0% |

| British Columbia | 4.8% | 2.8% | 1.5% | 2.2% |

| Yukon | N/A | 1.7% | 0.0% | 1.6% |

| Northwest Territories | 11.8% | 9.9% | 0.0% | 2.5% |

| Nunavut | N/A | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.6% |

Figure 44 illustrates that, while the percentage of dwellings classified as crowded is slightly higher among Métis than among the non-Indigenous population in some regions (e.g., Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Yukon), the opposite is true in other regions (e.g., Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta, British Columbia, and the Northwest Territories). Overall, the crowding gaps between Métis and the non-Indigenous population are very small across the country.

Text alternative for Figure 44: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2016, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0.8% | 0.3% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.0% | 0.5% |

| Nova Scotia | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| New Brunswick | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Quebec | 0.4% | 1.1% |

| Ontario | 0.6% | 2.4% |

| Manitoba | 0.8% | 2.5% |

| Saskatchewan | 1.4% | 1.5% |

| Alberta | 1.2% | 2.0% |

| British Columbia | 1.0% | 2.2% |

| Yukon | 2.0% | 1.6% |

| Northwest Territories | 1.3% | 2.5% |

| Nunavut | 0.0% | 1.6% |

As shown in Figure 45, outside Inuit Nunangat, crowded dwellings are similarly rare for Inuit and the non-Indigenous population. Inside Inuit Nunangat, while crowded dwellings are still rare among the non-Indigenous population, more than a quarter of Inuit households are crowded in Nunavut (28.6%) and Nunavik (27.2%), with significant crowding among Inuit dwellings in Nunatsiavut (8.2%) and Inuvialuit (6.6%) as well.

Text alternative for Figure 45: Percentage of dwellings classified as crowded, 2016, Inuit and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Nunatsiavut (Labrador) | Nunavik (Northern Quebec) | Inuvialuit Region (NWT and Yukon) | Nunavut | Outside of Inuit Nunangat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inuit | 8.2% | 27.2% | 6.6% | 28.6% | 1.3% |

| Non-Indigenous | 0.0% | 1.7% | 2.0% | 1.9% | 1.8% |

Housing – dwellings in need of major repair

Similar to living in a crowded home, living in a home that is in need of major repair can have adverse impacts on well-being, both directly (e.g., if mold is present) or indirectly (e.g., by creating financial or mental stress, being disruptive, or depriving people of the household facilities on which they dependFootnote 34).

Figure 46 illustrates that there is a significant housing repair gap between Indigenous and the non-Indigenous population, with the largest gaps being evident among Registered Indians living on reserve and Inuit.

Text alternative for Figure 46: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair,2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair | 40.0% | 12.2% | 12.3% | 21.8% | 10.3% | 6.0% |

As Figure 47 illustrates, the percentage of dwellings in need of major repair decreased for the non-Indigenous population, Registered Indians living off reserve, Non-Status Indians, and Métis. Moreover, the gaps between these Indigenous groups and the non-Indigenous population narrowed slightly. By contrast, the percentage of dwellings in need of major repair rose for Registered Indians living on reserve and Inuit, and their gaps relative to the non-Indigenous population widened slightly.

Text alternative for Figure 47: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair,2001 – 2016, Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, Canada

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Inuit | Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 36.9% | 16.2% | 17.3% | 20.1% | 14.9% | 7.8% |

| 2006 | 42.2% | 15.4% | 14.5% | 22.4% | 12.5% | 7.0% |

| 2011 | 39.7% | 14.4% | 13.2% | 25.1% | 12.1% | 6.9% |

| 2016 | 40.0% | 12.2% | 12.3% | 21.8% | 10.3% | 6.0% |

Region matters

There are important regional variations in the housing repair gaps between the non-Indigenous population and Registered Indians living off reserve and Non-Status Indians, particularly in the Northwest Territories. When considering First Nations populations, however, it is the gap for Registered Indians living on reserve that has the most striking regional variations, going from a low of 21.0 percentage points wide in Nova Scotia to a high of 42.0 percentage points wide in Manitoba (Figure 48).

Text alternative for Figure 48: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair, 2016, First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Registered Indian on reserve | Registered Indian off reserve | Non-Status Indian | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 28.3% | 9.0% | 9.2% | 6.1% |

| Prince Edward Island | 30.8% | 14.6% | 13.9% | 7.5% |

| Nova Scotia | 29.4% | 11.6% | 16.0% | 8.4% |

| New Brunswick | 32.7% | 11.7% | 15.6% | 7.9% |

| Quebec | 31.9% | 10.3% | 11.2% | 6.2% |

| Ontario | 37.4% | 11.2% | 13.6% | 5.8% |

| Manitoba | 48.8% | 15.6% | 15.3% | 6.9% |

| Saskatchewan | 48.0% | 12.3% | 11.8% | 6.9% |

| Alberta | 46.7% | 10.3% | 8.6% | 5.1% |

| British Columbia | 33.2% | 12.5% | 11.3% | 5.8% |

| Yukon | N/A | 23.0% | 10.8% | 9.4% |

| Northwest Territories | 47.1% | 28.8% | 23.7% | 9.9% |

| Nunavut | N/A | 14.3% | 0.0% | 11.6% |

As Figure 49 illustrates, the housing repair gap between Métis and the non-Indigenous population was relatively consistent across regions, with Métis dwellings in all regions being at least somewhat more likely to be in need of major repair.

Text alternative for Figure 49: Percentage of dwellings in need of major repair, 2016, Métis and non-Indigenous populations, by region

| Métis | Non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 9.5% | 6.1% |